The shadow of a KC-135 Stratotanker.

The shadow of a KC-135 Stratotanker as it takes off before opening ceremonies at an air show June 16, 2024, at Columbus, Ohio. (Staff Sgt. Mikayla Gibbs, Air National Guard)

From miles above the midwestern prairies, I got a first-hand look at the machinery of doomsday.

Lying on my stomach in a pod beneath the tail of a KC-135 Stratotanker I watched as the operator next to me guided the flying boom behind us toward an aircraft keeping pace just below. This was a midair refueling mission, and the boom would top off the tanks of the receiving aircraft. That plane, with its white upper fuselage and black nose, was an EC-135 airborne command post, code named “Looking Glass.”

I’ve been thinking about that flight lately as the anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki again approach. On Tuesday, it will be 79 years since the U.S. destroyed Hiroshima with an atomic bomb, followed three days later by the bombing of Nagasaki. More than 200,000 people were killed, mostly civilians. The bombings hastened the end of World War II but heralded the passing of our technological innocence — we finally had the power to annihilate ourselves as a species.

For 29 years, beginning in 1961, a Looking Glass plane was airborne 24 hours a day to serve as a flying command post in case all ground systems were knocked out by nuclear war. A key part of America’s Cold War strategy, Looking Glass was capable of directing bombers and launching missiles from silos and submarines on orders from the president.

I remember the checkerboard of snow-covered fields far below us, how cold and cramped it was inside the boom pod, and how large Looking Glass seemed below us. It was, in fact, the same size as the tanker, both having been built on the airframe that would later be used for the Boeing 707 passenger jet. I was impressed with the skill of the boom operator, who made refueling the world’s most powerful command aircraft seem easy. On the underside of the stubby black wings of the flying boom, easy to be read from the cockpit of the aircraft being refueled, was the nickname of the Air National Guard 117th Air Refueling Squadron: “Kansas Coyotes.”

I had requested to be a journalist observer on a Stratotanker mission because I wanted to see for myself components of the nuclear arsenal that would, the thinking went, assure the destruction of the Soviet Union in case of an attack. I had boarded the tanker at Forbes Field in Topeka, but had not known until we were airborne that the mission was to refuel Looking Glass somewhere over the upper Midwest. A few weeks earlier I had sat in a B-52 Stratofortress — America’s heavy, long-range nuclear bomber — but was disappointed when that mission was scrubbed because of weather.

I’m not sure where we were, exactly, as Looking Glass was being refueled, but I believe we were over Iowa. At the time, in the 1980s, the global nuclear stockpile was at its height, with six powers holding more than 64,000 warheads. Russia and the United States owned most of those weapons, the result of a decades-long arms race.

Americans were more worried about nuclear war than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis. The 1983 ABC television movie “The Day After” captured the cultural anxiety by depicting more or less realistically a Soviet nuclear strike on Lawrence and the launching of retaliatory Minuteman missiles from silos in surrounding farmland. Directed by Nicholas Meyer and starring Jason Robards, it was the most-watched television movie in American history, with an audience estimated at 100 million.

But many critics panned it as bad drama.

“It was so bad the first hour,” said critic Marvin Kitman, “that you found yourself rooting for the bombs as they landed in downtown Kansas.”

Perhaps he meant “hometown” Kansas, but no matter. Few in the audience were rooting for nuclear holocaust. To judge “The Day After” as a bad movie because it goes nowhere after the missiles fly misses the point. There are no heroes, and certainly no winners, in a nuclear exchange. There is nothing to root for because ultimately what’s left, after unimaginable suffering, is ashes.

“The Day After” was a television event, one that may have changed the course of history by starting a national conversation about the consequences of nuclear war. As a young journalist, I was prompted to find out more about America’s nuclear arsenal and eventually won a grant to go to Japan and interview the aging survivors of the nuclear bombings there. I’ve written about that previously, in a column on the 76th anniversary of the bombings. What I learned from those who survived the bomb was that the horror was “beyond imagination.”

The global stockpile of nuclear weapons has gone down steadily since 1986, to a low of about 9,300 in 2017, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. But while the stockpiles have gone down, the number of nuclear powers has grown and now includes India, Pakistan and North Korea. In 2023, the Bulletin moved the hands of its Doomsday Clock to 90 seconds to midnight — the closest to catastrophe in the clock’s 77-year history.

This year, the clock remains at 90 seconds.

“Ominous trends continue to point the world toward global catastrophe,” the Bulletin said in its 2024 statement. “The war in Ukraine and the widespread and growing reliance on nuclear weapons increase the risk of nuclear escalation. China, Russia, and the United States are all spending huge sums to expand or modernize their nuclear arsenals, adding to the ever-present danger of nuclear war through mistake or miscalculation.”

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

Both the U.S. and Russia have modernized, or are in the process of modernizing, their nuclear arsenals.

The U.S. is estimated by the Bulletin to have 3,708 warheads and Russia, 4,380. Russia is just finishing the modernization of their stockpile while the U.S. is engaged in a years-long expansion.

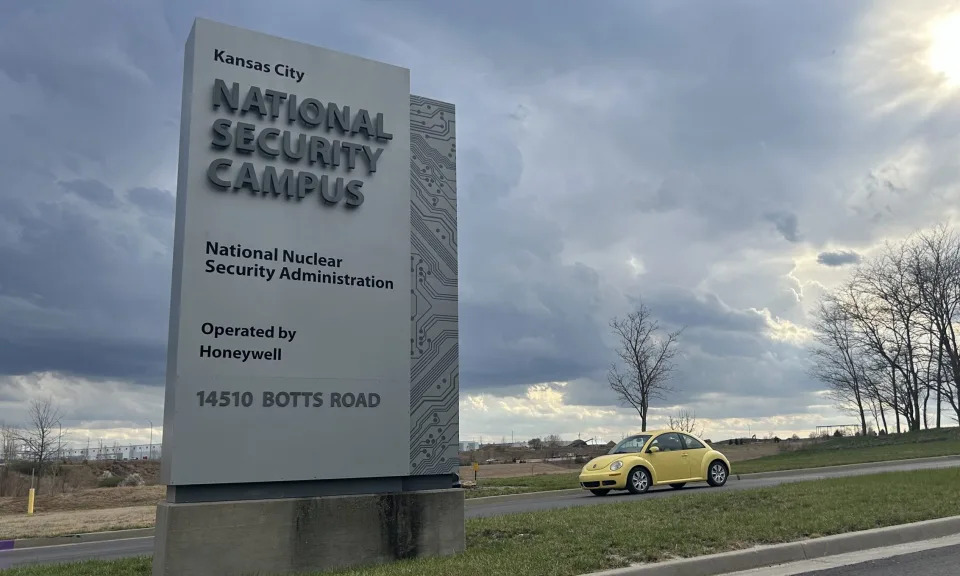

A key part of that expansion is a nuclear weapons plant in Kansas City, Missouri. Although it has the innocuous-sounding name of the Kansas City National Security Campus, it produces electronic components used in U.S. nuclear weapons. Since 2014, its workforce has gone from 2,400 to more than 7,000 to support the modernization program. The Kansas City plant, owned by Honeywell, recently completed the first production unit of the Mark 21 replacement fuse for Minuteman III and Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missiles. These modern weapons are many times more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which would today be considered low-yield weapons. To gauge the destructive power of a nuclear strike on your hometown, use Nukemap.

While part of the rationale for modernizing the American arsenal is safety — some of the warheads in the stockpile are 50 years old — the other part is deterrence. Despite the end of the Cold War, the doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction continues. We find ourselves in a new arms race, one that aims to keep existing stockpiles stable but make new weapons out of them that are more reliable and precise, and hence deadlier.

Nobody has yet come up with a satisfactory name for this era, so the New Cold War may have to suffice. But that harkens back to the days of the long standoff between the U.S. and Russia, doesn’t take into account the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and ignores the smaller and more unstable nuclear powers, especially North Korea. Complexities abound, each bringing a greater risk of catastrophe.

To understand our current era, we must avoid the metaphors of the past. Russia is still our most formidable nuclear rival, but now there are others, thick as dragon’s teeth. We may not even be aware of all of the nuclear powers now, because a well-funded (or well-connected) faction would have the means of obtaining a tactical device.

We find ourselves in a Midnight War — a struggle in the dark with multiple scenarios that for years we’ve been sleepwalking around, and time is running out.

With the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed possible that we were finally on the road to global disarmament. By 1991, the Doomsday Clock had been moved back to 17 minutes before midnight, reflecting the optimism that followed the signing of arms reductions treaties.

“The illusion that tens of thousands of nuclear weapons are a guarantor of national security has been stripped away,” the Bulletin noted.

This era of cooperation may have been aided by the uncensored airing, in 1987, of “The Day After” on Soviet state television.

The EC-135 — the kind of Looking Glass plane the Kansas Coyotes refueled while I was a civilian observer — was retired in 1998. They were replaced by the Navy E-6B Mercury, which performs a similar command post function under a new program.

I still have a framed certificate from the Strategic Air Command, also now defunct, recognizing my flight. It’s in a box somewhere, along with various other mementos of my early career. I keep it because it’s a reminder of a time when it nuclear disarmament seemed possible.

Yet, the nuclear threat remains with us.

We have failed to put Oppenheimer’s genie back in the bottle.

There was a time when we might have done it, when nuclear war was part of the national and even global conversation, when a communal “television event” could shake us from our sleep. Now it would be more difficult, considering that television, like all other media, has been shattered and the shards reassembled into billions of personal screens.

What we need is a new “Day After” moment, something that will demand our collective attention for 120 minutes on what is still the most serious threat to the survival of the human race.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...