Does China risk losing it all as it plays both sides in Myanmar's lengthy civil war?

China has invested heavily in neighbouring Myanmar over the years, especially in its infrastructure - from ports and railways to the oil and gas sector - even after a military coup rocked the country in 2021.

Myanmar has also played a vital role in China's ambitions for direct access to the Indian Ocean, as Beijing seeks to reduce dependence on the narrow chokepoints of the Strait of Malacca for its oil imports.

As Myanmar's prolonged civil war between the ruling junta and armed ethnic minority groups becomes increasingly violent and destabilising, Beijing has re-emerged as a top mediator for its war-ravaged neighbour, seeking to promote peace talks while protecting its geostrategic and economic interests.

In a flurry of diplomatic moves in recent weeks, Beijing has stepped up engagement with incumbent and retired leaders of the junta following the military's heavy losses in a battle near the Chinese border with a loose alliance of ethnic minority rebel groups.

Unlike its recent efforts to facilitate peace in the Middle East and in Ukraine, where China's limited involvement was largely "strategic and long-term", Beijing's push for reconciliation talks in Myanmar is clearly driven by acute security concerns, according to observers.

Yun Sun, the director of the China Programme and co-director of the East Asia Programme at the Stimson Centre in Washington, said Beijing's stepped-up role in Myanmar stemmed largely from the rebel takeover this month of Lashio, capital of the China-adjacent border state of Shan, marking one of the biggest victories for the anti-junta forces since the coup.

"[It] is a watershed event that will lead to more conflict. China has more influence on both the military and the rebels than any other country, or any other conflict, so China is in a strong position to mediate," she said. "The question is how."

China has been pushing both sides for talks to end the hostilities near its border, according to local media reports, with the junta and the rebels said to have reached a ceasefire in January after meeting in Kunming, capital of China's southwestern Yunnan province bordering Myanmar.

China's top diplomat Wang Yi travelled to Myanmar on August 14, becoming the highest-ranking Chinese official to meet junta chief Min Aung Hlaing since the coup.

Wang's visit, followed by a trip to Thailand for a regional meeting with Mekong River states, followed Chinese special envoy Deng Xijun's meeting with the Myanmar junta boss in Naypyidaw two weeks ago, and the arrival of Beijing's new ambassador Ma Jia last week.

In Beijing on Tuesday, Wang met Julie Bishop, the special envoy of the UN secretary-general on Myanmar. China supported the UN in playing a constructive role in the political settlement of the Myanmar issue, he told Bishop, whose visit came at China's invitation.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi with Myanmar's military chief Min Aung Hlaing, in Naypyidaw on August 14.

Sun said that China's recent moves, and Wang's trip to Myanmar in particular, were apparently aimed at "stabilisation and demonstrating China's support for stability and for elections, which China sees as a way out".

"More than economic projects, China does not want an unstable warring state on its border, especially as chaos and anarchy have created security threats for China such as through the cyber scam centres we have seen in northern Myanmar," Sun said.

However, "peace will not be easy to achieve, especially given the military's refusal to compromise", she cautioned.

China's interests in its southern neighbour, which shares a land border of over 2,000km (1,243 miles), are not limited to economic projects - Beijing has provided a lifeline for Myanmar's military since the late 1980s.

Amara Thiha, a Myanmar researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, said China's main focus was the protection of its investment projects in Myanmar, many of which were located in conflict-affected areas.

"China has mechanisms in place for protecting investments in conflict zones, however Myanmar presents unique challenges due to its proximity to the Chinese border," he said.

What is at stake for China in Myanmar is not just its vast geoeconomic interests, but also its ties with the junta amid doubts and distrust about Beijing's interference, according to Yin Yihang, a fellow on Myanmar affairs at the Taihe Institute, a Beijing-based think tank.

"The current situation in Myanmar is rather critical and complicated, after the junta's loss of Lashio, the headquarters of the northeastern military command, posing a major challenge to the momentum of the military and the legitimacy of its government," Yin said.

While it has yet to officially recognise the junta, Beijing has refused to condemn the coup, which saw the ousting of the elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi, and remains a major arms supplier in the face of Western sanctions.

Since a renewal of large-scale fighting after January's Chinese-brokered ceasefire collapsed in June, Beijing has accelerated its mediation efforts with a string of diplomatic moves in recent weeks in a bid to bring the warring parties back to the negotiating table.

Following his visit to Myanmar, Wang, who is China's foreign minister and President Xi Jinping's top foreign policy adviser, called the situation there "a cause for concern".

Addressing foreign ministers from Myanmar, Laos and Thailand in the Thai city of Chiang Mai on August 16, Wang said China supported a plan by the junta towards political reconciliation while relaunching the "process of democratic transition through elections".

During their meeting in Naypyidaw on August 14, Wang and Min Aung Hlaing "exchanged views openly regarding ... free and fair multiparty general elections", according to the junta.

A readout from Chinese state news agency Xinhua did not mention the long-delayed elections, which the junta has promised to hold several times since the coup, including its latest pledge in July.

"As a friendly neighbour, China opposes chaos or conflict in Myanmar, opposes external forces interfering in Myanmar's internal affairs, and opposes any remarks that attempt to sow discord in China-Myanmar relations or smear and vilify China," Xinhua quoted Wang as saying.

In a message aimed at both sides of the conflict, Wang called for deepening cooperation to implement several Chinese-funded megaprojects that are under threat from the escalating conflict, notably the China-Myanmar economic corridor and an oil and gas pipeline project.

Myanmar is part of the China-Laos Railway project, which is intended to connect Southeast Asian countries with the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan through a series of high-speed railways.

Jason Tower, a Myanmar expert at the United States Institute of Peace, said Wang's statement on maintaining "effective operation" of the cross-border pipelines underlined Beijing's mounting concerns about the junta's ability to protect China's interests and projects.

China's southwestern provinces have become reliant on the 800km twin oil and gas pipelines linking the Kyaukphyu deep-sea port in the war-hit state of Rakhine with Yunnan, which was signed off by then vice-president Xi during a Myanmar visit in 2009 and became operational in 2013.

"Over the past year, the Myanmar army's rapid collapse and repeated battlefield losses all along the geostrategic corridor along which the pipeline project runs have generated major security concerns for China," Tower said.

The junta has lost more than 30,000 sq km (11,583 square miles) of territory along the vital trade corridor between China and Myanmar in just over a month between late June and early August, according to Tower.

Following the fall of Lashio, he said the balance of power between the rebels and the junta had "shifted significantly" in favour of the former, meaning that China now needed to rely much more on resistance actors to secure its interests and achieve stability.

"These developments have pushed China to get much more deeply involved in trying to influence the trajectory of the conflict, and to increase pressure on belligerent parties to keep China's strategic interests out of the crossfire," he said.

Vicky Bowman, director of Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, said Chinese government-to-government investments in Myanmar had been more affected than investments from other countries because of their location in areas affected by the conflict.

"However, many of them, particularly proposed dam, port and transport infrastructure projects, were still only at feasibility study stages. They were already facing delays and challenges even before the coup, so there has been little real impact on operating assets other than the pipeline," said Bowman, a former British diplomat who was based in Yangon till 2022.

Of far greater economic significance is the disruption to cross-border trade in agriculture, fisheries and natural resources from Myanmar and manufactured goods from China, according to Bowman.

"This has badly impacted the private sector in both countries," she added.

Wang's trip, however, "showered Min Aung Hlaing's regime with legitimacy and sent strong signals to all of Myanmar's resistance actors and to neighbouring countries that China continues to see his regime as the primary national authority," Tower said.

But it also laid bare tensions between Beijing and the junta amid anti-Chinese sentiment that runs deep in Myanmar.

Ahead of Wang's visit, Beijing was visibly annoyed by Min Aung Hlaing's public remarks, in which he accused unspecified "foreign" sources of arming rebel groups.

The junta chief "implied that Chinese interference had resulted in his army's defeat ... which he used to spark anti-China protests" targeting the Chinese-speaking rebel groups that were central to driving the junta out of Shan state, Tower said.

"Wang delivered yet another warning to the military regime not to stoke anti-China sentiment, and the official Chinese readout of the meeting stressed the need for Myanmar to provide security to its economic interests in the country, implying that the Chinese government is no longer confident in the Myanmar army's ability to do so," he added.

Thiha, at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, also noted that Beijing's opposition to "external interference" was aimed at some rebel groups, such as the pro-democracy People's Defence Force, which had close connections with the US and other Western countries.

"China perceives these developments as potential security threats along its border," he said.

Soon after Wang's visit, during a virtual meeting between US officials and Myanmar's shadow National Unity Government, Washington voiced support for the pro-democracy opposition and promised to maintain pressure on the junta.

Thiha, who has experience easing dialogue in Myanmar, said: "China possesses the most significant leverage among all external stakeholders in Myanmar, both economically and politically. Its active engagements, particularly with northern groups and the current regime, underscore its influence."

But Beijing's much-touted economic leverage and influence and the prevailing perception in Myanmar regarding China's ties with the Three Brotherhood Alliance of ethnic armed groups - may also hamper its efforts to present itself as a neutral facilitator of peace, he said.

China's often-proclaimed stance of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs, a cardinal rule in its foreign policy, also limits its ability to advocate for structural changes as part of Myanmar's peace process, like Western mediators often do, Thiha said.

Yin, from the Taihe Institute, also agreed that despite tensions between Beijing and the junta, it was unlikely that China would abandon the Myanmar military.

"No matter how bad the Myanmar military is on the battlefield, solving Myanmar's problems cannot be separated from the military - you can leave Min Aung Hlaing and other military leaders, but you can't leave the military as a whole," he said.

"China's influence on ethnic armed groups is actually not that great. We asked them not to fight, but they didn't listen. China is now in a situation where it is difficult to please both sides."

Zachary Abuza, a Southeast Asia expert and professor at the National War College in Washington, agreed that Wang's visit came at "a very sensitive time," when the Myanmar military was "in terminal decline" while rebel groups controlled nearly the entire border with China.

"[China is,] no doubt, frustrated with the junta's incompetence and battlefield losses that have undermined China's economic interests," he said.

Although Beijing deserved credit for investing time and effort and calling for a new ceasefire agreement, Abuza said that China had not yet accepted the ground truths, making their strategy "doomed to fail".

"I am very sceptical of China's mediation efforts. Beijing is still pushing for a nationwide election as an off-ramp for the junta. But this is a very naive policy," Abuza said.

"It assumes that Min Aung Hlaing will agree to it, which is unlikely; he will continue to stall. It assumes that polls could be held, but the opposition controls over half the country and has no incentive to hold polls."

But Beijing was expected to continue to play both sides in Myanmar by supporting the embattled junta, while arming the ethnic rebels at the same time to maintain some control and influence, he said.

"China desperately needs a political solution to the end of the civil war, or everything it has poured into the country is wasted."

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

‘Are we not eating tonight?’ Myanmar’s military junta accused of using hunger as a ‘weapon’ by blocking vital food aid

Khin Mar Cho worries for her 4-year-old son as she struggles to scrape together enough food to feed him in a makeshift displacement camp at a crowded monastery in western Myanmar.

Soldiers had stormed their village of Byine Phyu, Rakhine state, and forced her and other family members out of their homes. They detained all the men and shot her brother and other neighbors, she said.

Survivors like Khin Mar Cho fled to the monastery just outside the regional capital Sittwe. There, a lone monk is struggling to feed about 300 people who have sought refuge inside the camp as a three-year civil war intensifies around them, waged by Myanmar’s military junta against an armed resistance.

“There are days that we have no food, even though we are hungry,” Khin Mar Cho said. “I cannot feed my kid anything more than meals donated by people because I don’t have a job or income, and all the male family members have been taken away.”

Disturbing accounts from multiple aid workers suggest hunger is being used as a weapon of war in Rakhine state.

The junta is preventing aid from reaching desperate people by imposing checkpoints, blocking roads and waterways, and refusing to issue access permits to humanitarian groups, multiple senior United Nations officials, and local and international aid workers in Rakhine told CNN on condition of anonymity because most weren’t authorized to speak.

Rakhine has become a focal point of the conflict, where a powerful ethnic minority armed rebel group, the Arakan Army (AA) — which is accused of human rights abuses — has seized control of at least 10 of the state’s townships since a year-long ceasefire with the military collapsed in November.

The aid officials said the junta is trying to “starve” civilians in AA-held territory, using tactics that have repeatedly been described as war crimes and crimes against humanity by UN officials and rights groups.

“They are using food as a weapon,” a senior aid official told CNN. “That much is clear.”

In a statement to CNN, Myint Kyaw, Deputy Permanent Secretary for Myanmar’s Ministry of Information, alleged rebel groups — not the junta — are restricting “people’s access” to territories they control.

“The Myanmar government is committed to the equality of all citizens,” the statement said. “Every citizen has the right to travel freely without any restrictions.”

Risk of starvation

Aid workers say they don’t know the full extent of the suffering due to telecoms and internet blocks coupled with restrictions on access to affected areas.

But they say the crisis is acute.

The situation unfolding across the country is desperate, but in Rakhine — which is almost entirely dependent on food aid — the UN says that fewer than a quarter of the 873,000 people who need food assistance have received it.

“There is a very real possibility that the most vulnerable… may die if they do not receive support,” a UN report warned in June. It is now August, and the situation has deteriorated.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

Displaced residents in Rakhine told CNN they are growing increasingly desperate as they and their families struggle to cope with escalating violence and dwindling supplies of food and medicine.

Prices for basic staples, like rice, fuel and cooking oil, have skyrocketed partly due to shortages created by the junta’s control of supply routes north from Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon, aid officials said. Requests to transport goods, including food, into the region are being refused, they added.

Meanwhile, food production in the state has plummeted, with farmers predicting a 50% drop in this year’s rice harvest, independent Myanmar news outlet The Irrawaddy reported.

Mohammed, a 43-year-old father of three, has lived in a displacement camp with his family in Sittwe since 2012, when anti-Muslim violence forced tens of thousands of people from their homes.

The latest fighting has not yet reached Sittwe, which the junta still controls. But since the collapse of the ceasefire deal between the AA and the military in November opened a major new front in Myanmar’s civil war, the camp has been all but cut off and conditions have drastically deteriorated, he said.

Mohammed’s children attend a small, makeshift school within the camp, but he says it’s difficult to nurture their dreams when he can only feed them half a bowl of rice.

“My children would cry and ask, ‘Are we not eating tonight?’ In those moments, feeling desperate, I would go to a neighbor and ask for some food to feed our children,” Mohammed told Partners Relief and Development, an aid NGO.

Yet his neighbors are hungry too, and they have little to spare.

Access denied

Shayna Bauchner, a researcher at Human Rights Watch, told CNN the junta is obstructing aid deliveries in Rakhine by blocking roads and waterways, seizing relief cargoes and confiscating medical supplies.

“As the conflict has spread around Rakhine, we’ve also seen the destruction of roadways and bridges,” she said. “The result is, basically, no one has access to these places.”

Aid groups, including UN agencies, must get “travel authorizations” from the state government, which reports to the ruling military council, before they can access territory that the junta considers “travel-restricted areas,” according to aid officials.

In February, the junta stopped issuing nearly all travel authorizations to contested or rebel-controlled territory in the state, most of which are in northern Rakhine, according to seven aid officials with direct knowledge of the matter, all of whom requested anonymity.

Without the travel authorizations, it’s impossible to pass through the junta’s road and waterway blockades, they said.

One senior aid official said, “it is difficult to negotiate because the SAC does not want assistance to go to non-SAC controlled areas,” referring to the State Administration Council, the official name of the junta government.

In May, some aid agencies received travel authorizations for Sittwe when the junta allowed them to begin transporting supplies from Yangon. Two cargo vessels carrying rice and basic medicine arrived in Sittwe two months later, but some items such as solar lights, hygiene and newborn kits remained held up, OCHA reported in August.

Teams still can’t access the surrounding townships or areas further afield.

“No official travel authorization has been granted to humanitarian partners to implement activities outside of Sittwe township since November 2023,” a senior aid official told CNN.

Seeking to broker an end to the blockade, senior UN officials held informal talks with SAC officials last month in the country’s capital, two sources told CNN.

The UN aid officials made clear in their meetings, which have not been previously reported, that the status quo is unacceptable, the sources said. Separately, the two officials said the issue was raised with the UN Security Council, the European Union and China, among others.

The junta told humanitarian groups that it cut their access to AA territory because aid workers cannot safely travel through areas the military does not control, sources told CNN.

But “that’s a lame excuse,” said a senior aid official. “We don’t need the junta to cover for our security.”

Local aid workers caught trying to deliver food and supplies in junta-controlled territory without a permit have also been arrested, those on the ground told CNN.

Aid workers and officials say the junta’s blockade is part of a wider war strategy long used by the military, designed to chip away at the rebel group’s popular support by cutting off food, water and medical care to the civilian population.

Bauchner, the Human Rights Watch researcher, said the blockades are “deliberate, and they are intended to harm the population in what is an apparent war crime.”

Myint Kyaw of the junta’s information ministry, said humanitarian groups are “being allowed to go to safe areas” after completing a verification process and alleged — without evidence — that rebel groups are blocking aid deliveries.

In the statement, the junta linked instability in the region to armed groups allegedly engaging in online gambling, planting and selling illegal drugs, human trafficking, online scams and illegal weapons deliveries to “terrorist groups” in rebel-controlled areas.

But one local aid official who works in northern Rakhine said the junta is “punishing civilians collectively” by blocking most food and medicine imports. Even the limited food that is available in the state is prohibitively expensive to most, largely thanks to blockade-induced inflation, he said.

“People are surviving on the bare minimum … like rice and salt,” said Ejaz, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym for his safety.

“I’ve seen it with my own eyes.”

War and hunger

Many of the displaced in Rakhine are members of the stateless Rohingya minority, who have been persecuted for decades in a country that denies them citizenship.

Jamila, 26, a former resident of the predominantly Rohingya town of Buthidaung, close to the Bangladesh border, said the community recently suffered food shortages for at least six months due to the fighting.

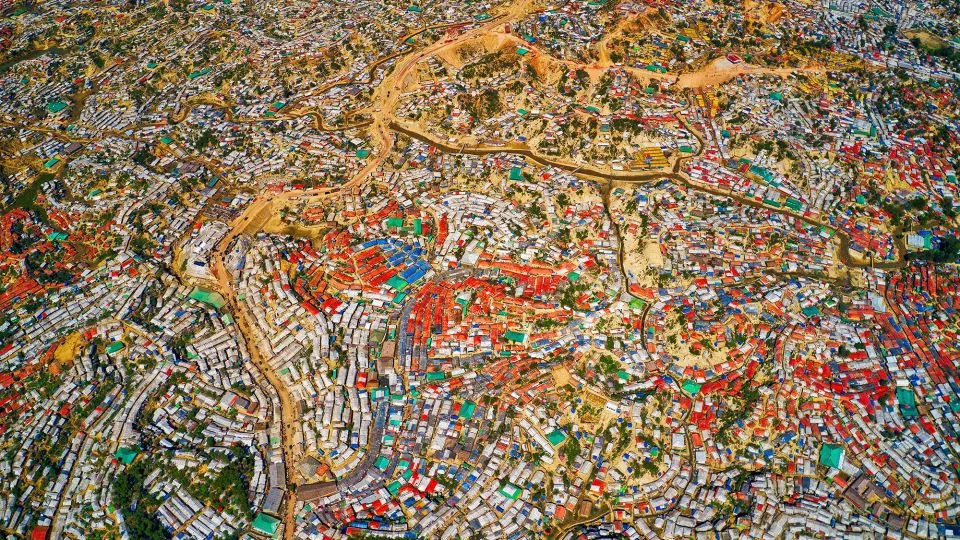

“No one came to give us food. The junta blocks all roads. They block all aid trucks,” said Jamila, who goes by one name and spoke to CNN from a refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, where her family recently fled.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

Many shops were looted by fighters and soldiers, she said, and those still open could only get supplies by smuggling them at high prices across the border from Bangladesh.

Food supplies were also strained as droves of displaced people from surrounding villages fled to Buthidaung to escape fighting and landmines.

“Everyone was helping everyone,” she said. “I lived life with risk and hunger.”

With little food and no medicine, Jamila said her children suffered from diarrhea and vomiting. “I am suffering from allergies. My whole body is full of itching. But there is no medicine, no treatment,” she said.

In late May, the Arakan Army said it seized Buthidaung. Activists and relatives of residents accused AA soldiers of extrajudicial killings, torching and looting Rohingya neighborhoods, and forcing thousands of people to flee.

Jamila said fighters stormed her village, drenching her home in petrol and setting it on fire while she and her family were still inside.

As the flames consumed their home, they scrambled to grab what belongings they could salvage — but only those on the ground floor had time to flee. Her parents-in-law, asleep in their beds upstairs, did not make it out.

They had no time to mourn. As they ran to escape their village, the howl of gunfire rang out, and a bullet pierced her younger brother. He did not survive.

“We didn’t try to save him,” Jamila said. “We were hearing the screams of people, the cries of children.”

She walked for six days to reach Bangladesh, saying “we lived by eating banana leaves and drinking pond water.”

CNN could not verify Jamila’s account but it matches other reports from the incident.

In a statement, the AA denied it torched Buthidaung, saying it “adheres to its principle of fighting under the military code of conduct and never targets non-military objects.”

Earlier this month, the AA was accused of killing Rohingya people in drone strikes and artillery fire as villagers fled the nearby town of Maungdaw. It denied involvement and blamed the deaths on the Myanmar military and allied Rohingya armed groups.

CNN reached out for comment to the AA and the Humanitarian and Development Coordination Office (HDCO) of the United League of Arakan (ULA), the AA’s political wing.

In a statement to CNN, the HDCO said there are about 590,000 people displaced in Rakhine state, according to their data, but civil society organizations are only reaching 20-30% of conflict-affected people.

“Emergency responses are extremely slow. The ULA government, including HDCO, is making every effort to provide food, shelter, water, and healthcare with the limited resources available,” it said.

“The primary challenge remains the acute shortage of essential supplies, including food, non-food items, medicines, medical equipment, women’s dignity kits, agricultural products, seeds, and fuel.”

The HDCO, which said its primary focus is on data collection, emergency response, monitoring aid requirements and tracking aid distribution, said junta blockades and risk of aerial bombardments means “there are instances where we are unable to reach those in need.”

‘We are invisible’

When the junta blocks official aid deliveries, regional and local humanitarian groups use covert tactics to operate without approval from the military, risking their lives to deliver aid to those in need, according to officials at four local aid groups, all of whom declined to publicize their tactics because it could jeopardize their operations.

But it’s far from enough.

At least 18.6 million people — about one third of Myanmar’s population — need humanitarian assistance this year, but aid workers have only been able to reach 2.1 million, according to an OCHA report published last week. Even in territories that the junta does not blockade, intensifying war, record-low funding and international apathy are also limiting aid workers’ access.

Aid workers have also become targets in the junta’s war.

A World Food Programme (WFP) warehouse in Maungdaw was looted and burned in June, depriving that community of urgently needed food aid. But WFP’s local partners were already struggling to reach their warehouses in Rakhine because “artillery shells are falling everywhere,” according to a source with direct knowledge of the matter.

Junta-imposed restrictions on communications are also limiting aid workers’ ability to operate, they say. Signal, a popular encrypted messaging app, has become inaccessible to users in Myanmar unless they use a VPN (virtual private network), four Yangon residents told CNN. Junta police are also conducting random phone checks throughout the city, one resident added.

Meanwhile, the UN’s humanitarian response program in Myanmar is among the most underfunded in the world. UN agencies and their local partners estimate that about $1 billion is needed to fund aid efforts in the country through 2024, but they have only raised about 20% of that amount.

“In the best-case scenario, based on my discussions with the donors, we may raise 30-35%, though not beyond that, by the end of the year,” Sajjad Mohammad Sajid, the OCHA Head of Office in Myanmar, told CNN. “This is the second year in a row that Myanmar is facing a significant decrease in funds despite rising food insecurity.”

Without an immediate injection of cash and a lifting of the blockade, aid officials say they will be forced to choose who does — and does not — receive humanitarian aid, leaving millions of desperate civilians without urgently needed assistance.

“Underfunding will result in livelihoods falling beyond the point of repair,” the OCHA report warned.

A senior UN aid official in Myanmar blamed the funding shortfall in part on international apathy. There are relatively few global advocacy groups and international news outlets consistently reporting on the country, and unlike Gaza and Ukraine, human rights abuses in Myanmar have gained little international attention, he said.

“We have become invisible,” the official said. “Donors will find it difficult to fund missions that are invisible.”

The monastery in Sittwe, where Khin Mar Cho and her family now reside, relies on food donated from the local community.

Another villager from Byine Phyu, who declined to be named for safety reasons, told CNN that on good days they are given two basic meals of rice and vegetables, but her two children, aged 11 and 7, often go to bed hungry.

“The soldiers took all the money we had,” she said. “All we need at the moment is aid and support to survive this.”

Though his small monastery is overwhelmed with displaced people, the monk said he tries to collect more donations from the community, hoping to feed those in the compound more than small helpings of rice.

But they receive meager food donations. Adding to the dire situation, his makeshift camp is overfilled, many families are forced to sleep outside without a covering in the height of the rainy season, so sickness and diarrhea is rife, the monk said.

“There are no NGOs or medics helping them,” he said.

“The only help we get is from the fire service for their funerals.”

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Игры

- Gardening

- Health

- Главная

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Другое

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy