‘Biggest Outage’ In History: How China Can Blackout Global Communications Network & Put The World In Chaos

A series of murky incidents from the Baltic Sea to the Red Sea, related to the ongoing conflicts between Russia and Ukraine on the one hand and Israel and Hamas on the other, seem to have resulted in apprehensions of these being repeated between China and Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific.

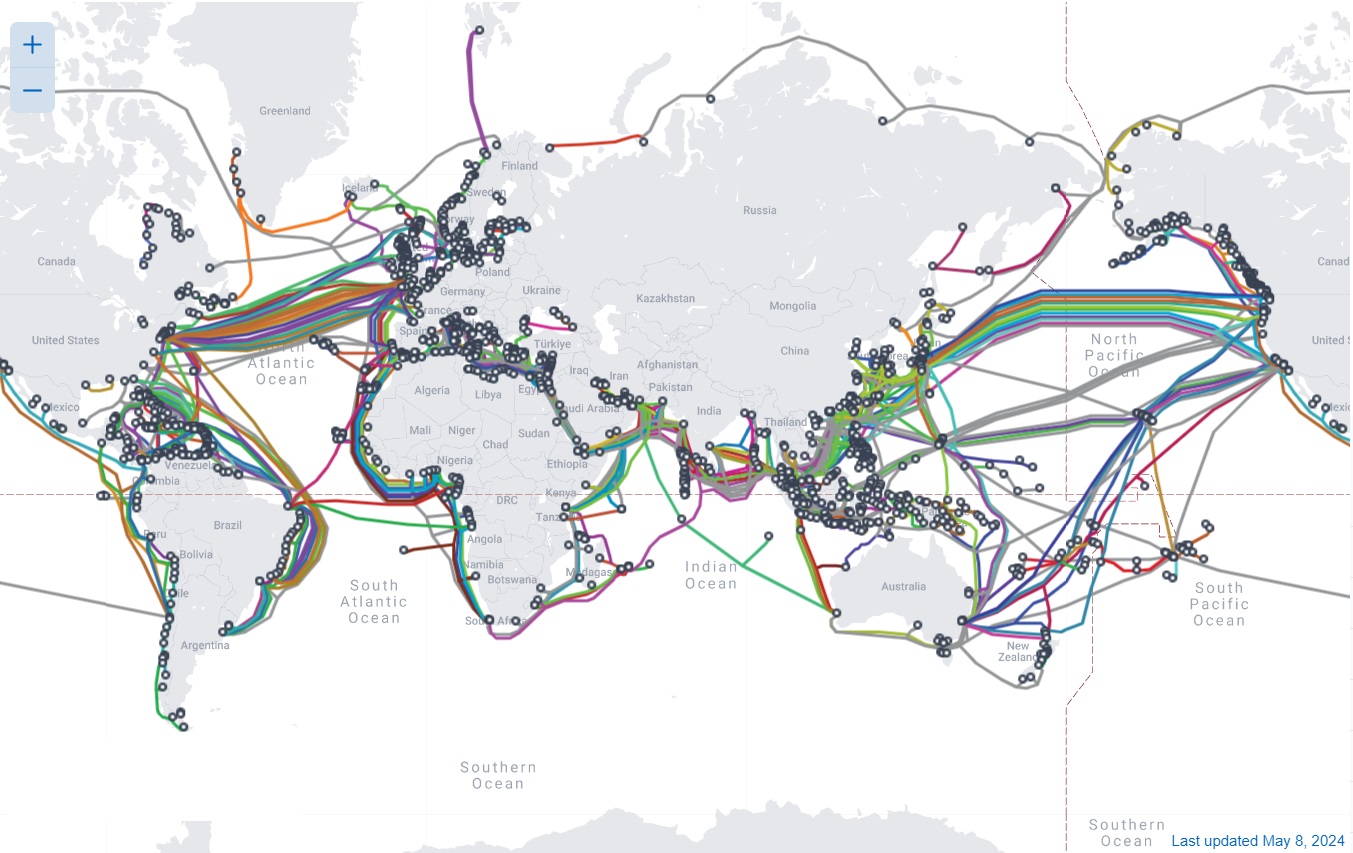

These incidents, which have occurred or are likely to occur, expose the vulnerability of the security of undersea /submarine cables, which carry most of the world’s internet traffic in a data-driven world.

These cables are said to be the arteries that connect nation-states and their people in literally every human activity, including trade, commerce, entertainment, and social interactions.

A recent US Congressional Research Service (CRS) report revealed that commercial undersea telecommunication cables carry about 99% of transoceanic digital communications, including international voice, data, internet communications, and financial transactions.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

In fact, global communications via satellites are minuscule compared to transoceanic ones. Individual private companies and consortia of companies own and operate a network of over 500 commercial undersea telecommunication cables that form the backbone of the global internet.

Any interference in their flow can disrupt lives and livelihoods and compromise the capacity of nation-states to trade, communicate, and fight wars, it is feared.

These cables, typically between two and seven inches thick and having a lifespan of approximately 25 years, are laid by slow-moving ships. Wrapped in steel armor, insulation, and a plastic coat, they contain fiber threads capable of transmitting data at 180,000 miles per second.

Reportedly, the entire global network of cables, consisting of more than 600 active or planned submarine cables crisscrossing the world’s oceans, is more than half a million miles long, enough to go from Earth to the Moon more than three times. The recent explosive growth of cloud computing has vastly increased the volume and sensitivity of data—from military documents to scientific research – crossing these cables.

It is against this background that the Nord Stream pipeline attack in September 2022, initially alleged to be done by Russia but now increasingly believed by Western experts to be carried out by the Ukrainians, highlighted the vulnerability faced by such cables.

In March this year, Yemen’s Houthi rebels allegedly attacked three cables running through the Red Sea to express their solidarity with Hamas. These cables, incidentally, provide connectivity for the internet and telecommunications across Asia, Africa, and Europe. The attack cut the cables and reportedly affected 25 percent of the communications passing through the Red Sea from Asia to Europe.

Based on these recent incidents, now it is feared that a Chinese attack on Taiwan would involve China disconnecting the island from America and the world by severing undersea internet cables, making defense and coordination much harder.

In fact, in May, the Wall Street Journal carried a report of U.S. officials warning some big tech companies like Google and Meta about potential vulnerabilities in the undersea cables that carry internet traffic across the Pacific Ocean.

Apparently, the warning followed the American security officials noticing Chinese repair ships, particularly those operated by S.B. Submarine Systems (SBSS), a state-controlled company, intermittently hiding their locations near Taiwan, Indonesia, and other coastal areas from radio and satellite tracking services.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

https://www.amazon.com/Africircle-AfriPrime/dp/B0D2M3F2JT

Silicon Valley giants like Google and Meta own and rely on specialized construction and repair firms, including foreign-owned ones, to lay fiber-optic cables on the seabed. Now, U.S. officials fear that the Chinese repair ships could potentially engage in data tapping, mapping the ocean floor for reconnaissance, or theft of intellectual property used in cable equipment. There is also concern that these ships might lay cables for the Chinese military.

Of course, developing offensive seabed warfare capabilities is not exactly new. Nations have had a fleet of nuclear submarines designed to carry smaller nuclear submarines that can interfere with seabed infrastructure deep below the surface. But now there are autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that could be launched from hundreds or even thousands of miles away, approach their target unseen, and blow it up.

Of course, there are two ways these cables get broken: intentional and natural. According to TeleGeography, a U.S.-based telecommunication market research firm that tracks and maps undersea cables, there are globally, on average, 100 to 150 cable breaks a year. The majority of incidents (about 75%) are caused by human activities, mainly fishing and anchoring. About 14% of cable breaks are caused by natural events (e.g., earthquakes), and 6% by equipment failure.

The remaining incidents of damage to undersea telecommunication cable systems are intentional, done by enemy countries or organizations. And their number, based on the recent incidents and trends, is likely to grow, it is apprehended.

According to the Economist magazine, Russia has invested heavily in naval capabilities for underwater sabotage, primarily through GUGI, a secretive unit that operates deep-water submarine and naval drones.

The magazine has quoted a report published in February by Policy Exchange, a think-tank in London, claiming that since 2021 there have been eight “unattributed yet suspicious” cable-cutting incidents in the Euro-Atlantic region, and more than 70 publicly recorded sightings of Russian vessels “behaving abnormally near critical maritime infrastructure”.

More than the sabotage, the U.S. and its allies fear snooping of their cable by the adversaries, something they themselves have been doing for decades if the Economist is to be believed.

“In the 1970s, America conducted audacious operations to tap Soviet military cables using specially equipped submarines that could place and recover devices on the seabed. As the internet went global, the opportunities for underwater espionage rose fast. In 2012, GCHQ, Britain’s signals intelligence service, had tapped more than 200 fiber-optic cables carrying phone and internet traffic, many of which handily came ashore on the country’s west coast. It also reportedly worked with Oman to tap others running through the Persian Gulf. The lesson—that the route and ownership of cables can be vital to national security—was not lost on others”, the magazine wrote.

The Americans’ greatest concern now is the fear of Chinese espionage in the Indo-Pacific, given what China has done and will do to Taiwan. If Elsa Kania of the Centre for a New American Security (CNAS), a think tank in Washington, is to be believed, the People’s Liberation Army would seek to impose an “information blockade” on Taiwan.

Apparently, in February 2023, a Chinese cargo ship and a Chinese fishing vessel were suspected of cutting the two cables serving Matsu, an outlying Taiwanese island, six days apart, disrupting its connectivity for more than 50 days.

A recent report by the Institute for Security and Development Policy, a Stockholm-based independent and non-profit research and policy institute, points out that China has started dominating the digital economy in the Indo-Pacific.

China, the report says, is rapidly expanding its digital infrastructure in the Asia-Middle East-Africa as part of the Digital Silk Route (DSR). The main objective of China’s DSR is to construct submarine cables globally to control data and information flow and to build digital infrastructure in developing countries by providing loans and credits.

The Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe (PEACE) cable is one of China’s big-ticket projects, which connects Gwadar Port with Djibouti, Kenya, Seychelles, and South Africa. The upcoming Africa project is also another massive Chinese project, an extensive 45,000 km long submarine cable to interconnect Europe, Asia, and Africa. China has also approached Pacific Island countries for building digital infrastructure with seamless connectivity.

However, China’s approach has raised concerns among many experts, given the country’s “coercive lending” process that creates a “debt trap” situation. In fact, Quad countries (Australia, India, Japan, and the United States) have expressed concerns about China’s growing involvement in the construction of submarine cables, especially when it comes to safeguarding the sovereignty and resilience of Indo-Pacific nations with less developed critical infrastructure.

The above report highlights how China is causing a delay in the approval for laying cables in the South China Sea. The country is demanding that companies obtain permits to carry out work in international waters outside of its territorial waters.

This has forced companies to consider alternative routes to avoid China’s interference. The Singapore-Japan Cable 2 (SJC2) project is one of the projects that has been delayed due to China’s actions. Due to Chinese assertiveness, two planned new cables from Singapore to America—Apricot and Echo—have been rerouted via Indonesia to avoid the South China Sea.

It may be noted that Chinese behavior led the Quad leadership in 2023 to adopt a resolution to support the regional “Quad Partnership for Cable Connectivity and Resilience,” which aimed to strengthen cable systems in the Indo-Pacific region by drawing on world-class expertise in manufacturing, delivering, and maintaining cable infrastructure.

Additionally, the U.S. “CABLES” program and the “Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment” between the U.S., Australia, and Japan are also expected to provide assistance in setting up safe and reliable cable infrastructure across the Indo-Pacific region.

In any case, submarine cables pose a significant governance challenge due to the absence of an international regulatory authority or framework to oversee them. Some experts favor the idea of establishing “cable protection zones,” which would ban certain types of anchoring and fishing and require greater disclosure by vessels inside them. Some also talk of solutions that include updating international law around cables and establishing treaties that would criminalize foreign interference.

However, all these options need global consensus. But that is a Herculean task as the U.S. and its allies, Russia and China, and important emerging powers like India have to be on the same page, something highly unlikely.

AfriPrime App link: FREE to download...

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Jogos

- Gardening

- Health

- Início

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Outro

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy