Three days ago, Lloyd Austin, the US Secretary of Defence, announced a naval coalition – dubbed Operation Prosperity Guardian – to defend Red Sea shipping from the recent escalation in “reckless Houthi attacks originating from Yemen”.

A satellite view of the Bab-el-Mandeb strait at the southern end of the Red Sea. Much of the world's maritime trade passes through the strait, now menaced by Houthi missile and drone attacks.

The Houthi attacks are working. The latest figures from maritime analysis provider MarineTraffic suggest that traffic through the Bab el Mandeb between 15 and 19 Dec is down 14 per cent from 8-12 Dec. If Prosperity Guardian is to succeed that figure needs to return to ‘normal’ for this time of year.

I should say straight away that the route to real success here, as ever, lies ashore between various governments and agencies who look at this issue across the entire region, albeit through their respective specialist lenses. The warship part of the problem that I’ll look at here fits into a much more comprehensive set of discussions and emerging plans.

So far, nineteen countries have signed up to Prosperity Guardian including the US, UK, France, Spain and Italy (these five have committed ships) plus Bahrain, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway and the Seychelles. Nine others do not want to be named for now: a clear indication of the region’s sensitivities. There are some notable absentees: India (although they might send ships), Egypt and Saudi Arabia, for example.

I thought I’d concentrate on what the Prosperity Guardian warships might be asked to do and why. On their own, they will struggle.

Of the countries providing surface combatant warships, the US are likely to have seven (with several in support), the RN has two (with four in support), France one, Spain one and Italy one. No one has formally declared their hand yet so these numbers are based on what is either in the area already or making good speed to get there. For now, let’s call it twelve surface combatants assigned to Prosperity Guardian.

In broad handfuls, there are two threats they will need to deal with. First, they need to defend against the missile and drone threat. So far, ships of the US, Royal and French navies have shot down 36 of these (with the US leading the charge by a distance with 34 kills). While this is impressive, missiles have got through causing damage and in the case of the Norwegian chemical tanker Strinda, starting a fire. How there hasn’t been a major spillage, sinking or fatalities yet is a miracle. There is also a fast attack craft threat (crewed or uncrewed) to be considered. This hasn’t been seen yet but will be familiar to any navy people who have operated in the region.

Second, the warships need to protect against piracy and hijackings of the sort attempted a few times now with success on two occasions. There is also the potential for a mine threat which is a whole different ball game if that comes into play.

The problem right at the start is that the requirements for these two tasks are quite different. The missile-and-drone task requires a line of ships up the eastern side of the Bab el Mandeb channel in clearly defined boxes. The size of these will be determined by the capabilities and range of each ship’s missiles but the aim is to provide a chain through which nothing can pass. One of the ships then acts as the area air warfare commander (AAWC). The AAWC ship coordinates the compilation of a Recognised Air Picture (RAP) across all ships and then allocates weapons accordingly when a threat is detected. This would be a perfect task for HMS Diamond because her radar is excellent but the US have the lead and they are quite mean when it comes to sharing tasks like this so it will likely be allocated to an American Arleigh Burke-class destroyer.

The piracy-and-hijacking task needs a more dynamic, mobile approach as defeating piracy as it is happening inevitably requires the warship to close at high speed and either warn off or disable the pirate boats or helicopter.

History has plenty of examples where tasking like this has been taken on. The classic convoy model of WWII can be discounted. There isn’t space and there aren’t enough ships. Operation Earnest Will of the late 80s in the Gulf was similar in terms of the threat but the number of ships that needed protecting was fewer. Operation Desert Shield in the early 90s had ships checking in at waypoints to be picked up by escorts and also saw merchant ships starting to embark their own missile defence systems, something that carried over to Operation Guardian Mariner in 2003. The anti-piracy efforts of the late noughties and early teens in the Gulf of Aden were over a larger area but more ships were available and the threat was much less sophisticated than what we have seen so far from the Houthis.

This mix of threats in a confined space isn’t unprecedented although the amount of ships that need protecting and the speed of attacking missiles may be.

My money is on a hybrid solution that sees some ships in boxes up the eastern channel and some with a roving commission to attach themselves to ships deemed to be of high importance and to intercept piracy attempts.

Aircraft will have a vital role in all of this, both in terms of contributing to the air picture but also for shooting down drones and engaging pirates. The surface warships have their own helicopters, but the US carrier Dwight D Eisenhower – Ike, now just to the south of the Bab el Mandeb in the Gulf of Aden – will bring hugely greater capability. However the US will not tie up a carrier on a task like this for the long term, so the surface warships will need to be able to do the job on their own.

In maritime terms the bottom of the Red Sea is small. But if you measure the distance from the southern to the northernmost attacks (so far) you are looking at 300 nautical miles. If you give each warship an ambitious 30 mile long box to protect, then you need ten ships for the missile/drone defence task alone. Some missiles carried by the various ships can theoretically cover much greater areas than this, but if a warship cannot detect a drone or a missile it cannot shoot at it: and a sea-skimming aircraft is below the horizon and thus unseen if it is at any great distance. There will also be ships in the task force which only have shorter-ranging missiles, so ten ships for the drone-and-missile barrier is a reasonable assumption.

Of course if you have ten ships on line you need more assigned to the force because they will need to refuel periodically, and at the current rate of missile expenditure, rearm as well. Then you add the roving ships for the piracy task and you quickly run out of ships. So you either make the boxes larger and therefore the defence more porous, or you protect a smaller area. These are the planning conundrums that staff officers in Bahrain will be wrestling with just now.

Then there’s the merchant-to-military interface, so that ships can pass through with the minimum of delay whilst still being protected. Sal Mercogliano does a good job on YouTube describing the complexities of this – there are many. So it will take a while to set this task up and then settle down – it always does. In the meantime you will continue to see some ships taking the option to reroute round the Cape of Good Hope or pause their passage whilst things become clearer.

Not enough warships, the sheer amount of traffic to protect and the complexity of the merchant-military interface are three reasons why I don’t think Prosperity Guardian will work on its own. It is entirely defensive in nature and thus ignores the other tried and tested way of ensuring the safety of ships at sea – destroying the enemy’s ability to threaten them.

That this hasn’t happened already shows just how complex the diplomatic situation across the region is right now. It is also partly because of the difficulties in striking the Houthis a) successfully and b) without escalating the conflict. This would not be the easy hit that many imagine.

Striking back requires precision. The Houthis have learned a great deal from their Iranian masters about mobility – there are no large warehouses or HQs marked “strike here”. So counter-strikes against missile and drone launchers or radar stations will need to be fast, or the target will have gone. This is possible but requires rapid intelligence-to-targeting processes: enter Ike, stage right.

Any attacks also need to be carefully paced if escalation is to be avoided. The Houthis have demonstrated this to perfection. They announced themselves with a bang on 26 October, followed by a few attacks on ships connected to Israel, then a few more on ships going to or from Israel before gradually crescendoing to the less discriminatory model seen today. The Houthis have caused maximum disruption without overstepping the mark and making a strike back unavoidable.

Allied attacks on them need to be similarly careful and the easiest way to do that is on a ‘one out, one in’ model, with launch sites/vehicles struck each time the Houthis make an attack. This can be justified on the international stage as self-defence and has the added benefit of eroding the Houthi will to fight. At the moment they are operating with impunity.

Between now and counter-strikes happening – if they do – Operation Prosperity Guardian is no better than a sticking plaster. Its entirely defensive nature does not appear to be winning over some shipping lines or navies. It is early days though, so the plan should be afforded the benefit of the doubt. However, absent a political or diplomatic solution, I believe that defensive measures will have to be combined with precise, non-escalatory counterstrikes to restore freedom of navigation in this critically important maritime chokepoint.

All of this could, of course, be overtaken by events. What effect will the anticipated (non UN-directed) operational pause in Gaza have, for example?

For now however, it is a sobering thought that a relatively minor terrorist militia group can threaten global trade in this manner. The situation should serve as a stark reminder to governments of the importance of investing properly in the measures required to prevent this from happening again. That is, in navies, to put it bluntly.

Tom Sharpe is a former Royal Navy officer. He was a specialist anti-air warfare officer, and commanded a surface combatant warship

US-led forces in Red Sea will be defensive ‘highway patrol’

Soldiers aboard the U.S.S. Mason have been actively protecting commercial ships in the Red Sea.

The longer container lines detour from the Red Sea around the Cape of Good Hope, the more vessel capacity will be soaked up, and the higher freight rates will go. Rates are already rebounding. New surcharges just announced by ocean carriers imply freight costs are headed higher still.

Container lines have a perfectly valid reason to avoid through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait from a corporate governance perspective: They cannot guarantee the safety of their seafarers, ships or cargo due to indiscriminate attacks by Yemen’s Houthi rebels.

From a bottom-line perspective, the timing couldn’t be better. The Red Sea-driven rate rise coincides with annual contract negotiations for Asia-Europe service that renew Jan. 1.

If disruptions extend for months, not weeks, they will impact negotiations for Asia-U.S. annual contracts that renew May 1. Numerous Asia-East Coast services that previously transited the Panama Canal switched to the Red Sea/Suez Canal route due to drought-induced restrictions in Panama.

The U.S. and its allies have unveiled Operation Prosperity Guardian in an attempt to convince shipping lines it’s safe to come back to the Red Sea, a move some analysts initially thought would bring a swift resolution, minimizing container rate upside.

But a press conference by Defense Department spokesman Maj. Gen. Patrick Ryder on Thursday offered little guarantee that disruptions will end soon — unless civil-war-hardened Houthis are easily cowed by tough talk.

‘Think of it as the highway patrol’

Ryder made no mention of full-scale military-escorted convoys for commercial ships. Rather, he said Operation Prosperity Guardian would provide expanded patrols, i.e., what the U.S. Navy is already doing, but with more warships and international partners.

“The [Houthis] have become bandits along the international highway that is the Red Sea,” he said. “And so, the forces assigned to Operation Prosperity Guardian will serve as a highway patrol of sorts, patrolling the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden to respond to and assist commercial vessels as necessary.

“The distance we’re talking about here, from the Suez Canal down to the Gulf of Aden, is about the distance from Boston to Washington, D.C., so you’re talking about a pretty extensive stretch of water that the international community will be covering.”

Asked whether the member nations of Operation Prosperity Guardian have the authority to attack Houthi targets in Yemen, or whether it is primarily a defensive operation, Ryder responded, “This is a defensive coalition. Again, think of it as the highway patrol to safeguard maritime.”

There was a veiled threat of retaliation, however.

“The Houthis need to stop these attacks,” Ryder said. “They need to stop them now. And they really need to ask themselves if they’ve bitten off more than they can chew when it comes to taking on the entire international community and negatively impacting billions and billions of dollars in global trade.”

‘Like 20 police cruisers trying to cover entire Pacific coast’

James Stavridis, vice chairman of global affairs at the Carlyle Group, addressed the shortcomings of an expanded-patrol-only option in an op-ed piece in Bloomberg on Tuesday.

“The sea space that the maritime operators must cover is remarkably vast. The Red Sea — from the Suez Canal to the Bab-el-Mandeb on the horn of Africa — is the size of California. To cover the rest of the North Arabian Sea and the approaches to the Red Sea, you can add another chunk nearly double the size of Alaska.

“Even if you had 20 warships on patrol — a very high number for a maritime mission — it would be like 20 police cruisers trying to cover America’s entire Pacific Coast,” wrote Stavridis.

“The U.S. and its partners may have to do more than put additional warships on defensive patrol,” he said. “We must be prepared to go on offense: to carry out offensive strikes against targets ashore … against Houthi infrastructure on the southern Arabian peninsula.”

Nightmare scenario: A ‘lucky strike’

Investment bank Evercore ISI held a client webinar on the Red Sea crisis on Thursday, featuring Michael Rubin, a senior fellow at think tank American Enterprise Institute and director of policy analysis at the Middle East Forum.

Rubin dubbed Operation Prosperity Guardian “military virtue signaling.”

His concern is that the crisis will escalate if the Houthis get a “lucky strike” that kills American Navy personnel.

“The nightmare scenario is … you have a situation like the U.S.S. Cole and there’s a lucky strike on an American ship and 30 people get killed or the ship is crippled. That’s going to change the dynamic in Washington, especially against the backdrop of an election campaign.”

According to Rubin, “The model in many people’s minds goes back to the counter-piracy efforts with regard to Somalia. There you had an international task force.

“The difference between that and what we’re seeing here is that off the coast of Somalia you were in deep blue territory — deep blue in terms of ocean depth and so forth. Therefore, the ships we were sending were largely out of range or they could hang out in areas that were out of range until they needed to move forward to render assistance.

“With the Bab-el-Mandeb, you’re going to be in range of almost anything when you enter that area. So, it becomes a much more difficult problem set for the U.S. Navy. It becomes vulnerable to drones. It becomes vulnerable to cruise missiles, and it becomes vulnerable to speed boats laden with explosives.”

Asia-Med spot rates rising fast

Spot rate indexes already show a significant effect from the Red Sea attacks.

The Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI) jumped 15% this week, driven by a 45% week-on-week surge in Shanghai-North Europe rate assessments.

The Drewry World Container Index (WCI) put average spot rates from Shanghai to Genoa, Italy, at $1,956 per FEU for the week ending Thursday, up 40% since the last week of November.

The WCI assessment for Shanghai to Rotterdam, Netherlands, was at $1,667 per FEU, up 42% over the same period. The WCI Global Composite was at $1,661 per FEU, up 20%.

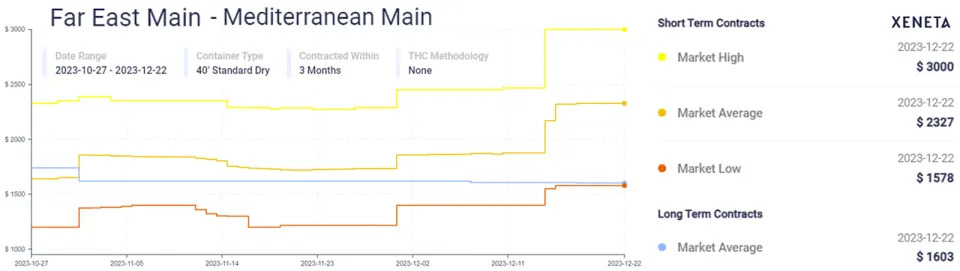

According to data from Xeneta, spot rates in the Asia-Mediterranean market averaged $2,327 per FEU on Friday, with the low spot rate at $1,578 per FEU and the high at $3,000 per FEU. The average spot rate was 45% above the average contract rate signed in the past three months of $1,603 per FEU.

The average Asia-Mediterranean spot rate has increased 34% since Nov. 30 and 24% since Dec. 14, according to Xeneta data.

Carriers tack on emergency charges

While rates are rising, ocean carrier profits will not increase to the same extent, because their costs are also up due to sudden diversions. Longer voyages hike fuel bills and other expenses.

Carriers are now tacking on charges to offset those costs.

MSC, the world’s largest ocean carrier, has introduced a contingency adjustment charge (CAC). It is adding a CAC of $1,500 per FEU on shipments from the Middle East and India to Europe starting Saturday, and $1,500 per FEU for shipments from the Middle East and India to the U.S. East and Gulf coasts starting Jan. 18.

MSC said that it was invoking clause 19.2 of its bill of lading, which states that it reserves the right to charge additional freight and is not responsible for delays.

Other carriers are adding similar charges.

Hapag-Lloyd added an emergency revenue charge of $2,000 per FEU on cargo scheduled to transit the Suez eastbound through the end of the month, and $3,000 per FEU on westbound cargo.

Maersk is levying a transit disruption surcharge of $400 per FEU for cargo on the water that was diverted from the Red Sea, and a peak season surcharge of $1,000 per FEU starting Jan. 1 for Asia-North Europe cargo, $2,000 per FEU for Asia-Mediterranean cargo, and $600 per FEU for Asia-U.S. East Coast cargo.