New Views of Why Age Accelerates Time. Several new theories of why one person senses time differently than another. Reviewed by Davia Sills

KEY POINTS-

- Decades ago, time seemed to move more slowly than it does now.

- Rapid eye movement can affect our sense of time.

- Biophysical changes can change our perception of the speed of time.

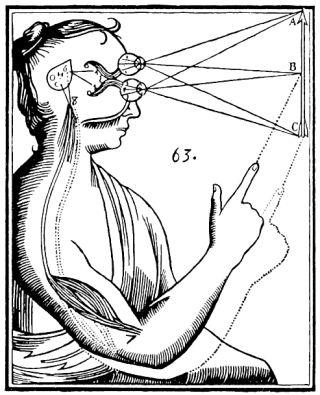

Yesterday’s thought-provoking blog posting by Kurt W Ela, “How to Slow Down Time (No, Really)”, gives an alternate view and reason for time-speeding with age. One theory, Ela tells us, is that the cognitive impression of time’s speed is connected to how we process visual information. He cites Professor Adrian Bejan’s paper in the European Review, “Why the Days Seem Shorter as We Get Older,” from which we learn one reason time seems to accelerate with age: Biophysical changes happen. In particular, he attributes it partly to saccade frequency (rapid movement of the eye), body size, and neuronic pathways degradation.

In 2021, during that anxious period when COVID was at our back doors, I posted a blog titled “Does Anyone Know Time?” that centered on issues of a divided, confused, and fearful nation. We are no longer in the COVID era that once filled us with hard-to-cope-with anxieties, but rather in a limbo of other worries akin yet different from those of the 1960s. Coming out of the COVID era, the U.S. is still divided and confused with worries ranging from mass shootings to the annoyances of political immaturity. We still have fires, droughts, hurricanes, and floods that threaten our habitats.

I wrote that time moved slower during the 1950s and '60s than it does now. That’s true to my perception and the opinions of many people I surveyed for my book on that subject. Just take the speed of personal communications through mail and telephone. As a young boy studying in France in 1961, I would go once a week to the American Express office to check if there was any mail sent from home. Calling home? Forget it! At that time, a 3-minute call would cost $50 ($500, adjusted for inflation).

One old theory, attributed to the 19th-century French philosopher Paul Janet, has it that time accelerates by a person’s proportion of life lived. But time seems different for us now than it did when we were younger because something far deeper happens with age. The theory of time awareness as proportions of age, both conscious and subconscious, is rational, but that kind of sentience is built on the memory of an entire life, albeit a blurry sketch of life.

It might simply be that with each passing year of life, our daily experiences are more repetitive and humdrum with fewer new ones of any lasting impact. We don’t pay much attention to routine experiences but do pay significant attention to salient ones, like a first kiss, a first car, a high school prom date, or a fall that chips a front tooth. They are landmarks on trails of lives. But salient experiences like those first kisses, cars, or graduations get less frequent with age. Possibly that’s one reason why we think time speeds up with age, though, by far, it is not the only reason.

We are far too complex to have our time senses solely guided by a single series of common actions. The causes are not so simple. Whatever steers the time’s sense of accelerated passing must come from multifarious hierarchies of intricately related inner signals that interact with the body’s understanding of how the life we lead convolutes with time. One cause in the hierarchy is a person’s activity. The active life gives the impression that time is moving slowly, contradictory with the notion that boredom makes the clock run excruciatingly slow. That activity is intimately connected with body time, the pulse, the heartbeat, the body temperature, the muscle memory as well as brain activity. Time sense is one giant ball of interconnected feedback from the way we live.

I find Bejan’s connection to saccades inspiring. I know that the eye tells time and relays what it knows to an area of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a pair of nuclei in the hypothalamus at the center of the brain, a place very close to the pineal gland. That gland produces melatonin to regulate heart rates, sleep patterns, and body temperatures. The SCN gets its information from the eyes and passes it along to the cells of organs that work best in a circadian rhythm. It is the internal body clock. So, it is not surprising that saccades play a role in both the synchronization of time in the cells of the body as well as the cognitive impressions of the passing of time.

Thanks, Ela, for a new view of time and a few ways to slow it down.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Oyunlar

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy