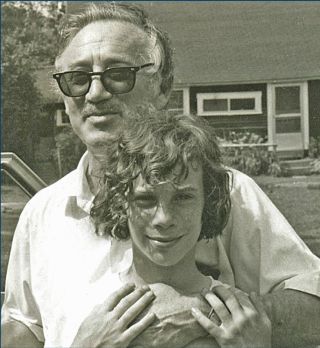

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives.” The line is actually deeply misunderstood. Experts will tell you Fitzgerald was suggesting he once believed that to be the case but then changed his mind, mocking the sentiment. As such, the author would be appreciative of my father, Morrie Schwartz, who has had numerous public lives, and a burgeoning amount of public recognition.

As a professional social psychologist, my father burst onto the academic scene with his work with renowned psychiatrist Alfred Stanton. The pair did a series of scholarly articles for Psychiatry XII (1949). Particularly “Medical Opinion and the Social Context in the Mental Hospital” was influential and reprinted in Psychoanalytic Quarterly (1950). The essay outlined how an administrative psychiatrist generally labors under a distorted stereotype of the hospital and decisions are often motivated by this stereotype. Needless to say, this conclusion pushed institutional psychiatric treatment forward at a time when institutions badly needed the shove. Notice the emphasis on understanding and relating to the person or reality, not the stereotype, or image society creates.

The pair then co-authored their seminal book, The Mental Hospital (1954). Based on research at Chestnut Lodge mental hospital, the work revolutionized how practitioners thought about mental hospitals and psychiatric treatment in general. My dad spent months in the institution observing the relationships between doctors, nurses, staff, and patients and the conclusions took people by surprise. The authors stated that the entire environment, and particularly the relationships of everyone involved, were crucial to the psychological state of the patient. Social Service Review summarized the perspective: “These studies thoroughly document the authors' thesis that the social situations and attitudes of the hospital environment (such as staff conflict) may 'cause' pathological symptoms and behavior.” This emphasis on the primacy of all human relationships in any given system, and the need to take special care of each relationship and interaction, would inform the rest of my father’s personal and professional life.

Dad received an appointment to full professor in the sociology department at Brandeis University in 1959 and remained at that institution, which he loved, until his emeritus in 1987. He authored two more books and numerous articles examining the problems and issues with mental health and psychiatric care, focusing on the entire social system a person exists in as well as their internal dynamics. But Dad did not feel academic work was enough. He saw many people who could not afford, and or were too intimidated to seek, mental health care. For this reason, he co-founded Greenhouse with Phil Slater (then famous for his book The Pursuit of Loneliness) and Jackie Doyle in 1971.

Greenhouse was a low-cost, free personal growth center where all people, regardless of economic status, could seek therapy in a highly supportive and non-judgmental environment. Dad’s previous observations on institutions provided insight for Greenhouse to take distinct care with every relationship. This approach particularly hit home for Slater, who had grown so disenchanted with academia that he resigned his professorship at Brandeis as chairman of the sociology department.

Dad’s concern for people’s well-being, and his emphasis on how he and everyone related to each other was a main theme that ran through his life. His favorite course to teach at Brandeis was Group Process. When he ran up against his final foe, ALS, Dad used these insights, sensibilities, and perspectives to create discussion groups around his own death, spirituality, and leading a good life. When his former student Mitch Albom reconnected with Dad and interviewed him for 12 Tuesdays it’s no surprise that the result was the sensitive, poignant, and insightful Tuesdays with Morrie (1997). Initially, the book was little recognized because my father was not a widely heralded public figure up until that point. But with help from Oprah, the pages skyrocketed to stratospheric heights. Called the best-selling memoir of all time, the volume has sold approximately 18 million copies and is translated into about 40 languages. My father’s lifelong perceptions on relating to people, presented through Mitch’s brilliant prose, was a grand slam. I can’t tell you how many people have burst into tears when they find out who my father is.

Now we have a further emanation of Dad’s great insights on how to lead a meaningful life and interact with people around us. The Wisdom of Morrie: Living and Aging Creatively and Joyfully is my dad’s last book. It was written between 1988 and 1992 after he hit the age limit for a professor at Brandeis (something that no longer exists). Dad uses his lifelong training to examine the internal repression and external stigma of ageism and age-casting (his coinage). I discussed the ideas with Dad while he was writing the manuscript and he was shocked by how he himself had internalized the poisonous prejudice of ageism. He recognized it in himself and in society and realized he needed to use his acumen to combat it. That was the impetus for this book. He noticed that society age-casts seniors. That is, it forces them into roles they may not want (the same way actors are typecast) and tries to keep them from wider participation in society.

To combat this, Dad suggests we all recognize how malevolent and wrong this is and seniors should take every opportunity to pursue whatever they are interested in. All of us, young and old, must cast out our ageist biases. Relate to the person, not the stereotype society creates. The book is filled with examples showing this, encouraging people to never give up on their potential, and that age is not the barrier some think. Dad offers strategies and techniques to become more vibrant, more creative, and more connected to life as one ages. Reflecting the theme, Dad found a new creative vein within himself and offers examples, stories, poems, quotes, articles, parables, and insights to inspire us. His commitment to live each day, and help others do so, is clear.

I have been inspired to try to carry on his work. Some talented producers and I are preparing a major benefit music festival, Onetopia, for 2024. The benefit festival will raise awareness about mental health with proceeds and donations going to foundations and charitable organizations concerned with that overarching problem. I think my dad would approve.