KEY POINTS-

- Pain resists and often eludes people's attempts to describe it in words.

- Fiction writers' creative metaphors for pain can help build a vocabulary useful to patients and doctors.

- Awareness of other people's pain can promote emotional learning and growth.

People can learn from pain, perhaps more from other people’s than from their own. Yet knowing what other people feel depends on their ability to describe their suffering in words. Pain’s defiance of verbal language can compound the physical suffering it involves. People in pain may not be believed, or they may be told—by people who are not hurting—that they should “suck it up.” In creating a shared language of pain, fiction writers can help because they craft descriptions designed to make pain imaginable.

Researchers across academic fields have observed pain’s elusion of language. In The Body in Pain (1985), literary scholar Elaine Scarry argued that so many authoritarian regimes use torture because torture victims struggle to describe the atrocities committed against them. In Scarry’s view, “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it” (Scarry 4). Pain is private, and talking about it requires building bridges between one’s inner world and the worlds of others. Cognitive literary scholar Marco Caracciolo believes that “because of [pain’s] private … nature, bodily pain is the quintessential example of the ineffability of experience” (Caracciolo 107). Communicating the feel of any internal experience is hard, especially one that hurts.

Like Caracciolo, historian Joanna Bourke points out that because pain defies language, many people try to describe it metaphorically. “By using metaphors to bring interior sensations into a knowable, external world,” she writes, “sufferers attempt to impose (and communicate) some kind of order onto their experiences” (Bourke 477). Grounded in bodily experience, pain metaphors can help to build medical knowledge. Scarry reports that Patrick Wall and W. S. Torgerson created the McGill Pain Questionnaire by interviewing patients and categorizing patterns in their metaphoric descriptions of pain such as “gnawing,” “shooting,” or “burning” (Scarry 7).

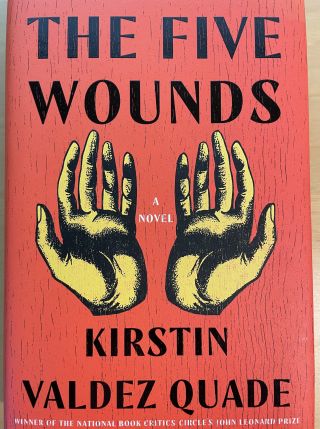

Fiction writer Kirstin Valdez Quade offers compelling descriptions of pain in her novel, The Five Wounds (2021). Her story shows characters learning from pain and depicts the physical and mental suffering of several people in a Northern New Mexico community. Amadeo, an unemployed alcoholic living with his mother, receives physical wounds when he is chosen to play Christ in a procession that reenacts Jesus’s suffering. Valdez Quade’s title refers to Christ’s wounds but also to the harm suffered by the interconnected community members. Amadeo’s daughter Angel becomes pregnant at 15, and the story follows the first year of her child’s life, from one Holy Week ritual to the next. Amadeo’s mother Yolanda, whose work sustains the family, has developed a brain tumor but can’t bring herself to tell anyone she is dying. Even more traumatic wounds become evident in Angel’s classmates in a school program for teenage mothers. In this far-from-wealthy community, everyone has suffered damage; the question is whether they can learn to communicate well enough to form supportive, sustaining bonds.

When Amadeo volunteers to have nails driven through his hands, the pain is not what he expects: “The pain is so immediate, so stunningly distilled, that Amadeo’s entire consciousness shrinks around it. He is no longer a man: only reaction, outrage, agony. He imagined the pain spreading through him like silent fire, unbearable in the most pleasurable of ways, like the burn of muscles pushed to their limits. He imagined the holy expansiveness that would swell in him until he was, finally, good. But instead there’s only this confused searing clamor, out of which rises a voice he only dimly registers as his own” (Valdez Quade 38). Amadeo has been hoping that by suffering physically, he can cleanse himself of his sins. Sadly, he imagines and experiences the pain in terms of the physical experience he knows best, that of alcohol (“stunningly distilled,” “spreading through him like silent fire,” “pleasurable in the most unbearable of ways”). There is nothing cleansing or enlightening about his excruciating experience. The phrase “searing clamor,” which links touch with sound, helps a reader to imagine pain so annihilating, it dissolves any agenda. It almost dissolves the self.

Yolanda, a more capable character, experiences her pain another way. The permanent headache caused by her tumor differs from the puncture pains of two nails, but her self-described sensations also reflect her work-filled life. Yolanda experiences her pain in terms of actions and spaces. While eating dinner with a friend, she sets “down her fork to press her head into her palms when the pain nearly scooped her eyes from their sockets” (Valdez Quade 44). In the night, she feels that “the pain in her head is too large to be contained by her skull” (Valdez Quade 75). Yolanda’s metaphors suggest an attack from within and without: an assailant is gouging her at a time when her body can no longer contain what it has been given to hold. The aging woman whose clerical work has sustained New Mexico, as well as her family, finds her boundaries collapsing. Like her son Amadeo, she feels herself dissolving, but she conveys her feeling through different metaphors.

Perhaps due to all the support Yolanda gave him, Amadeo survives and learns from both their pains. When the Passion ritual recurs and a young, recovering drug addict plays Christ, Amadeo reflects on his mistaken attitude toward pain the year before: “He pities his old self, the self that once believed there was a single, big thing he could do to make up for all his failings. He missed the point. The procession isn’t about punishment or shame. It is about needing to take on the pain of loved ones. To take on that pain, first you have to see it. And see how you inflict it” (Valdez Quade 404). The ritual of physical suffering is about everyone’s pain, not just one person’s, and maturity demands acknowledging the pain you cause as well as the pain you experience. Valdez Quade uses the classic metaphor of sight (“first you have to see it”) to represent any kind of learning achieved through perception, and she uses it for good reason. Yolanda and other characters in the novel don't talk about their pain. The reader knows about it only because the narrator shares their thoughts, to which Amadeo has no access. In a troubled year, he has started learning how to perceive pain that isn't expressed in language.

I have said that literary pain metaphors can potentially help doctors and their patients struggling to describe what they feel. The creative metaphors Valdez Quade crafts do more than show the differences between her characters’ personalities. Phrases such as “searing clamor” and “eyes scooped from their sockets” help to create a vocabulary through which anyone suffering or trying to relieve pain can communicate in order to learn what may be causing it. Pain can teach one about one’s relationships with others and about one’s community role. From pain metaphors, one can take the first step toward this learning by understanding what other people are feeling. Paying close attention to pain metaphors can help one imagine and relieve the pain of others.