KEY POINTS-

- Gut health and inflammation can affect mood and behavior.

- The gut is connected to the brain by the vagus nerve system.

- Neuroinflammation can disrupt signaling pathways in the brain.

When my son Marty was born, I wanted him to love the world. For a while, he did. He was quick to smile. He hugged dogs. He sprinted to school.

“Marty is so engaged and well-behaved,” his teacher said. “He wants to learn.” Marty had the right mindset.

Then something changed.

A new normal

When Marty was five, I noticed red spots in his toilet. The pediatrician thought it was from dairy. An allergist disagreed. The blood disappeared, but unexpected behaviors emerged.

Marty’s teacher called.

“It’s odd,” she said. “Marty can’t concentrate and won’t sit still.”

A psychologist observed. “He isn’t making good decisions,” she said.

She suggested weekly sessions with Marty and separate work with me. We focused on Marty’s mind, not realizing that his gut needed our attention.

Problems in the gut causing glitches in the brain

When Marty ate gluten (a protein in wheat, rye, and barley), his digestive system reacted like it was poison. Immune cells attacked and created chronic inflammation that weakened the lining of his gut. His body stopped absorbing essential nutrients while inflammatory molecules likely leaked out and entered his bloodstream.

“Inflammation that starts in the gut doesn’t stay in the gut. [It] can have a damaging effect on the brain,” said Dr. Emeran Mayer, a gastroenterologist and neuroscientist who is the director of UCLA’s G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience and who wrote the bestselling book, The Mind-Gut Connection.

“When immune cells are activated, the vagus nerve system sends a signal to the brain that can trigger fatigue and depression-like behavior,” Dr. Mayer said.

In kids, that can look like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), withdrawal, and irritability.

I didn’t see any microscopic cells in Marty’s gut send an SOS to his brain, but I noticed that my once energetic and happy boy had become exhausted and grouchy, opting out of activities that used to make him smile.

“Let’s go to the park.”

“No.”

“What about a play date?”

“I’m too tired.”

At school, small incidents became big problems.

“Marty doesn’t respect the rules,” his teacher said. “He won’t work.”

I had no idea that what looked like willful disobedience was an out-of-control situation in Marty’s microbiome. Neither did any of his doctors.

The psychologist suggested more intensive parenting training.

“You’re the key to helping him,” she said. But I came up short. Late arrivals to school turned into all-day absences and months of missed learning. I couldn’t get Marty moving.

"You’re making terrible choices!” I screamed.

By fourth grade, Marty quit school, sports, and seeing friends. His weight dropped, and his growth slowed. He was breathing but not living.

A puzzle I couldn’t put together

I couldn’t function. I stopped sleeping. I was desperate to catch the thief robbing my son of morning meetings, kicked soccer balls, and his mother’s comfort.

I often sobbed in the bathroom corner. One morning Marty heard and held my hand.

“I’m sorry Mom,” he said. “My brain feels confused. Why am I like this?”

I’m a reporter. I did what I know. I made calls.

Over five years, I consulted six child psychologists, two neuropsychologists, two social workers, one psychiatrist, Marty’s pediatrician, a sleep doctor, and six learning specialists. We did two full psychological evaluations.

“It’s ADHD,” one neuropsychologist said.

“It’s anxiety,” said another.

It didn't feel right to me, but the experts seemed sure.

“When an authority figure tells you something, as a mother with a child facing unexplained issues, you’re vulnerable,” said Susan Newman, a social psychologist and best-selling author. “You’re going to want to follow an expert’s advice,” she said. “But sometimes it’s best to trust your instincts.”

I knew I was missing something, but I went with recommendations for behavioral interventions and medicine. Every year, Marty got worse.

“What is happening?” I screamed to my husband. “This situation makes no sense!”

We were treating the wrong disorder.

Connecting the dots

When Marty turned 10, I begged the pediatrician to consider brain tumors, rare diseases, and cancer. He took vials of blood, and the result of one test told us all we needed to know. Marty had severe celiac disease with inflammatory markers higher than LabCorp could measure.

“Isn’t celiac a stomach problem?” I asked.

All of Marty’s doctors thought so.

As I wrote in this post, doctors don’t expect a gut disease to look like a mood disorder. But they should. Ninety percent of celiac patients reported psychiatric symptoms like “brain fog,” depression, and fatigue, in this nationwide study.

Research shows that activated immune cells in the brain can disrupt the signaling pathways that regulate neurocircuits and neurotransmitters, like dopamine and serotonin, which influence our motivation and mood.

“There are a ton of psychiatric patients that have inflammation, and it's not being addressed,” said Dr. Andrew Miller, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine. His research shows that, in some people, inflammation causes depressive behaviors but not enough doctors who diagnose psychiatric conditions consider causes outside of the brain or think beyond typical treatments.

“Psychiatry is too comfortable,” he said. “People follow along. It’s a herd mentality.”

That one-size-fits-all approach left Marty behind. It was only when he stopped eating gluten and his inflammation went away that his abilities returned. Now, 16 months later, he smiles, plays sports, and concentrates in class.

What Marty needs is simple and costs nothing.

JUST. NO. GLUTEN.

“The change is unbelievable,” his teacher said.

At home, Marty wakes up with a smile and gets out the door when I say in what feels like a whisper, “It’s time to go.”

Why not consider the gut when treating the brain?

When I told Marty’s doctors that removing the inflammation in his body fixed the problem in his brain, they thought I said abracadabra, not something scientific.

“There aren’t enough studies on celiac,” a therapist said.

But I found them in major medical journals like Psychiatric Quarterly and publications by the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The science is available. But there isn’t ample awareness.

“We’re not holistic enough,” one of Marty’s doctors explained. “The medical community is separate from the mental health community. Everyone is in their [silo].”

Psychiatrists fixate on the brain. Psychologists look at the mind. Pediatricians focus on the physical. But the body functions in an integrated system. When it comes to mental health, the gut is overlooked.

And there is no set standard to rule out underlying medical conditions like celiac or other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases that research suggests are more common in patients with psychiatric conditions, when making a diagnosis.

“The onus falls on the clinician,” according to the American Psychiatric Association. So does staying on top of new research. “Clinicians can attend training sessions [but] the gut and the brain are different groups.”

The system has blind spots, and, for Marty, the available treatment was missed. He's not alone. One in 100 people have celiac, and the majority don't know it. But that is likely to change.

“We are on the verge of a paradigm shift [in medicine]” when it comes to understanding the link between gut health, inflammation and the brain, said Dr. Mayer, the gastroenterologist at UCLA. “I guarantee that all of the textbooks will have to be rewritten,” he said.

Epilogue

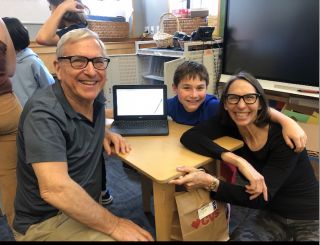

After three years of school avoidance and refusal, this year has been a breeze. Recently, I drove Marty to school.

“You used to have such a hard time getting here,” I said.

“You should stop thinking about the old me,” he said with a wide grin. “I’m different now.”

Marty has the right mindset, thanks to his healthy gut.

Tips

- Advocate. Looking back, I wish that I had done more for Marty. Demand that doctors become detectives if treatments aren’t working. Don't accept a diagnosis that doesn't make sense.

- Consider diet. Reducing inflammatory foods is linked to better health outcomes. Dr. Miller suggests following the Mediterranean diet. “Choosing what you eat matters,” he said. Consult a nutritionist about best practices.

- Do your own research. It typically takes 17 years for medical research to make its way to clinical practice. Read peer-reviewed medical journals and seek out doctors who are also researchers.