Future Indonesian president Prabowo Subianto's controversial past has raised questions inside China about what his approach to Beijing will be, but diplomatic observers broadly expect him to continue the current pragmatic stance.

Prabowo was a special forces general in 1998, when widespread anti-Chinese riots broke out that left over a thousand people dead across the country.

An Indonesian fact-finding team later found that elements of the military had instigated the attacks, which activists said were orchestrated to divert public anger away from the government led by Prabowo's father-in-law Suharto in the middle of a financial crisis.

Prabowo, now defence minister, has always denied involvement in the attacks, but they dominated discussions about his election on Chinese social media, raising concerns he might try to turn the country against China.

But an article on the social media account of the state-owned Xiwen Evening News dismissed these worries, adding that Indonesians had largely forgiven him for his chequered past, including his role in targeting protesters and dissidents.

According to unofficial tallies - which have proved relatively accurate in past elections - Prabowo has secured an unassailable lead over his two opponents in the race to succeed Joko Widodo.

He has signalled he will continue the brand of politics practised by the current president, usually known as Jokowi, and whose son Gibran Rakabuming Raka was his running mate. Most observers expect this to include the approach towards China.

Wang Yiwei, a professor of international relations at Renmin University, said China's ties with Indonesia had been "troubled" in the past, particularly under Suharto, who adopted an anti-China, anti-Communist stance.

"China is forward-looking," he said, citing a significant jump in Chinese investments in Indonesia which have included intensive infrastructure investments such as a high-speed rail link on Java that was opened by Widodo.

China is Indonesia's largest trading partner and it contributed US$3.6 billion in foreign direct investment in the first half of 2022, according to Indonesian government figures, while Chinese Premier Li Qiang committed US$21.7 billion in new investments when he visited Jakarta last September.

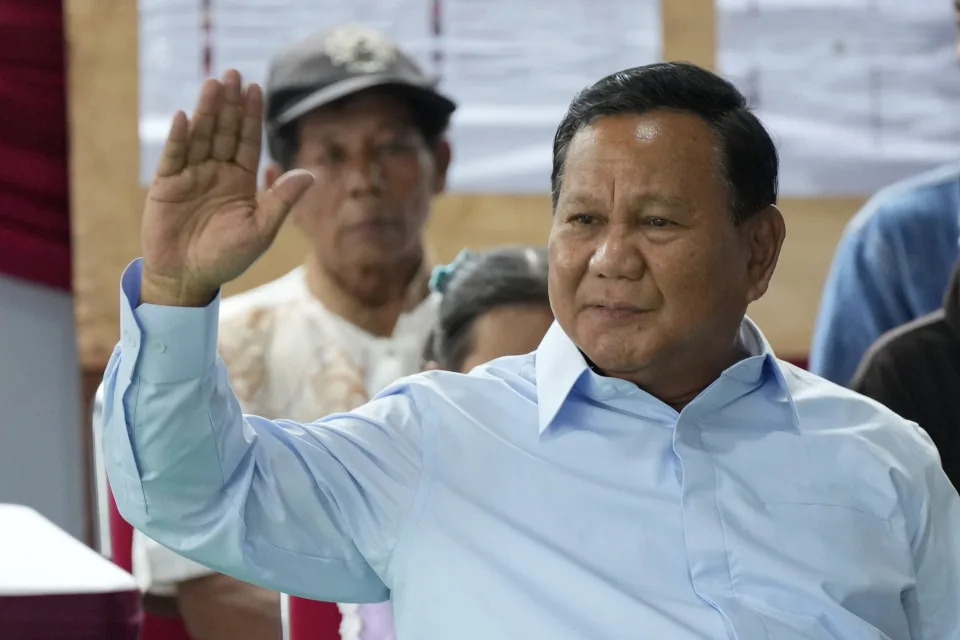

Prabowo Subianto, left, and his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the son of President Joko Widodo. Prabowo has pledged to continue the legacy of the man widely known as Jokowi.

Wang Huiyao, founder of the Beijing-based think tank Centre for China and Globalisation, said Prabowo might have had "some history ... but the situation has greatly changed" and relations were "much better".

He said China and Indonesia shared similarities such as belonging to the so-called Global South group of developing economies.

"I don't think any newly elected leader of Indonesia would treat China-Indonesia relations lightly," he said. "We need to look at the present and to the future. China-Indonesia relations are at an all-time high."

The success of the railway project launched last year - which Chinese state media described as carrying "historical significance" - showed the friendship between the two countries, according to Wang.

Lv Xiang, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said "history is history" when it came to the former general's past, but he said this may prove more of a problem in dealing with the United States and other Western nations compared with China.

During the Suharto era, Prabowo's unit was accused of kidnapping dissidents and student activists, some of whom have never been found.

He was dismissed by the military because of his involvement in these disappearances and the US banned him from entering the country until he visited as defence minister in 2020 because of these and other accusations concerning special forces operations in East Timor and Papua.

"This is a bigger problem that he may have to face," said Lv, arguing that Western countries may "take advantage" of Prabowo's past to pressure him.

He also expected Washington to try to shift Indonesia from a so-called "swing state" to one that supported the US.

Under Widodo's leadership, Indonesia - like most Southeast Asian states - has refrained from taking sides in the superpower rivalry and has maintained friendly relations with both.

He said Beijing saw Indonesia as an important bridge with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and expected political and economic relations to continue to develop.

"I personally do not see any negative signs," he said.

Indonesia analysts also said his past was unlikely to be a stumbling block to closer ties with China.

Muhammad Waffaa Kharisma, a researcher at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta, said the 1998 violence was aimed at ethnic Chinese "less so towards China, the state".

He said Widodo's foreign policy had been a pragmatic one and "ambitious and friendly" towards China, which has been a "major friend".

Although Prabowo has pitched himself as offering continuity, Muhammad Waffaa suggested that he could be a more active and present leader on the international stage but may prove more "erratic".

"We still need to wait until we see how Prabowo's impulses may shape our foreign policy, too, as it could be that Indonesian foreign policy can be further driven by the more pragmatic element of our free and active doctrine," he said, referring to the policy of trying to maintain good relations with all sides.

Yohanes Sulaiman, a political analyst at the University of Achmad Yani in West Java, said he did not expect a big change in Indonesia's foreign policy, but Prabowo is "far more nationalistic" than Widodo and may take a firmer stance on maritime conflicts.

Indonesia has long-standing disagreements with China over its exclusive economic zone off the Natuna Islands near the South China Sea, which Beijing claims almost entirely.

"He still maintains the reputation of a strongman who can get things done and somebody who is decisive ... he will not act like Jokowi in the South China Sea," Yohanes said. "He will be more forceful."

Prabowo Subianto pictured in 1998, when he was a special forces commander.

He said Prabowo needed to show the international community and businesses that he has a "consistent and predictable" foreign policy, but may feel obliged to respond to any provocations in the disputed waters.

Lv from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences said as long as Prabowo's government was sincere, such as in the development of its economy and infrastructure, its relationship with China "will only get better. I really don't see any difficulties so far".

Prabowo Subianto, a former general who was once banned from entering the United States because of alleged human rights abuses, looks set to become the next President of Indonesia, according to preliminary results hours after the Southeast Asian country of 270 million people voted on Wednesday in the world’s largest single-day election.

Prabowo cruising to Indonesia presidency halfway through count

Prabowo's supporters gathered outside his home to celebrate his apparent victory in the presidential election.

Indonesian Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto was on course to win the archipelago's presidential poll by a wide margin, official tallies showed Friday with more than half of votes counted.

The final result is not expected until late March but early indications all point to the 72-year-old ex-general succeeding popular outgoing leader Joko Widodo.

With more than half the ballots counted, Prabowo had a commanding 57 percent of votes, more than double his nearest rival and enough for a first-round majority, the election commission's website showed.

Former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan was on 24.98 percent on Friday morning and former Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo had 18.02 percent.

"Thank God, we must be grateful and continue to monitor the KPU's official results," Prabowo wrote on Instagram late Thursday, referring to the general election commission.

The fiery populist on Wednesday claimed a "victory for all Indonesians" alongside his running mate -- the current president's eldest son Gibran Rakabuming Raka -- based on preliminary results by government-approved pollsters.

The early sample counts -- previously shown to be reliable -- showed they were set for a first-round majority. Gibran, 36, would become Indonesia's youngest-ever vice president.

But both of his rivals said they would wait for the official result and had not conceded.

Prabowo needs more than 50 percent of the overall vote and at least a fifth of ballots cast in more than half the country's 38 provinces to officially secure the presidency.

Analysts said his win was almost assured.

Jokowi, as the incumbent leader is popularly known, told reporters Thursday he had met with Prabowo the previous evening to offer his congratulations.

He has been accused of backing his former rival and defence chief's campaign in a bid to install a political dynasty, via his son, before leaving office.

In his Instagram post, Prabowo said Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had called to congratulate him, as well as the leaders of Singapore, Malaysia and Sri Lanka.

Mark Rutte, leader of Indonesia's former colonial ruler the Netherlands, tweeted late Thursday he had congratulated the president-in-waiting because of the "projected outcome".

The United States was more cautious, only congratulating the Indonesian people on the election's "robust turnout" in a statement that did not mention Prabowo.

- Calls for justice -

Prabowo's election rivals have said they would investigate if there was any fraud in the vote, with Ganjar's team saying it had found "systematic" fraud, without providing evidence.

Anies on Friday visited Al-Azhar Great Mosque in the capital Jakarta, telling reporters "the deficiencies are various" in the vote count, also without providing evidence.

Reports of irregularities "can be seen on social media", he said, calling on people to report incidents to his legal team.

Holding one of the world's biggest single-day elections takes its toll on poll workers who count votes by hand, sometimes through the night, and deaths from overwork-related conditions and accidents are common.

At least 14 poll workers died from Tuesday to Thursday, according to local media reports Friday, citing local government, police and election officials.

While Prabowo supporters reacted with jubilation outside his home and at a packed arena in Jakarta after polls closed, activists whose children were shot dead or disappeared by military forces in the 1990s protested his win.

Non-governmental organisations and his former bosses accuse Prabowo of ordering the abduction of democracy activists towards the end of dictator Suharto's three-decade rule. More than a dozen have never been found.

Prabowo was discharged but has denied responsibility and was never charged.

Outside the presidential palace, more than a hundred protesters gathered late Thursday, holding up yellow cards, blowing whistles and unfurling a banner that read "save democracy".

One of them was Paian Siahaan, whose son Ucok disappeared in the last months of Suharto's rule, when Prabowo was a top commander.

Ucok was 22 when he went to a protest and never came back.

"This is beyond our prediction after following the campaigns and debates. We didn't anticipate that he would win by such a wide margin," said Paian, 77.

"So we are consoling each other."

Who is Prabowo Subianto, the former general who's Indonesia's next president?

A wealthy ex-general with ties to both Indonesia's popular outgoing president and its dictatorial past looks set to be its next leader. He's promised to continue the outgoing president's widely popular policies, but his human rights record has activists and some analysts concerned about the future of Indonesia’s democracy.

Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto presented himself as heir to the immensely popular President Joko Widodo, vowing to continue the modernization agenda that's brought rapid growth and vaunted Indonesia into the ranks of middle-income countries.

“We should not be arrogant. We should not be proud," Subianto said in a speech broadcast on national television from a sports stadium on the night of the election. “This victory must be a victory for all Indonesian people.”

But Subianto will enter office with unresolved questions about the costs of rapid growth for the environment and traditional communities, as well as his own links to torture, disappearances and other human rights abuses in the final years of the brutal Suharto dictatorship, which he served as a lieutenant general.

Other than promising continuity, Subianto has laid out few concrete plans, leaving observers uncertain about what his election will mean for the country’s growth and its still-maturing democracy.

A former rival of Widodo who lost two presidential races to him, Subianto embraced the popular leader to run as his heir, even choosing Widodo's son as his running mate, a choice that ran up against constitutional age limits and has activists worried about an emerging political dynasty in the 25-year-old democracy.

Subianto's win is not yet official. His two rivals have not yet conceded and the official results could take up to a month to be tabulated, but unofficial tallies showed him taking over 55% of the vote in a three-way race. Those counts, conducted by polling agencies and based on millions of ballots sampled from the across the country, have proved accurate in past elections.

Subianto was born in 1951 to one of Indonesia's most powerful families, the third of four children. His father, Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, was an influential politician, and a minister under Presidents Sukarno and Suharto.

Subianto’s father first worked for Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia’s quest for independence from the Dutch, as well as the first president. But Djojohadikusumo later turned against the leader and was forced into exile. Subianto spent most of his childhood overseas and speaks French, German, English and Dutch.

The family returned to Indonesia after General Suharto came to power in 1967 following a failed left-wing coup. Suharto brutally dealt with dissenters and was accused of stealing billions of dollars of state funds for himself, family and close associates. Suharto dismissed the allegations even after leaving office in 1998.

Subianto enrolled in Indonesia’s Military Academy in 1970, graduating in 1974 and serving in the military for nearly three decades. In 1976, Subianto joined the Indonesian National Army Special Force, called Kopassus, and was commander of a group that operated in what is now East Timor.

Human rights groups have claimed that Subianto was involved in a series of human rights violations in Timor-Leste in the 1980s and 90s, when Indonesia occupied the now-independent nation. Subianto has denied those allegations.

Subianto and other members of Kopassus were banned from traveling to the U.S. for years over the alleged human rights abuses they committed against the people of Timor-Leste. This ban lasted until 2020, when it was effectively lifted so he could visit the U.S. as Indonesia’s defense minister.

In 1983, he married Suharto's daughter Siti Hediati Hariyadi.

More allegations of human rights abuses led to Subianto being forced out of the military. He was dishonorably discharged in 1998, after Kopassus soldiers kidnapped and tortured political opponents of Suharto, his then-father-in-law. Of 22 activists kidnapped that year, 13 remain missing. Several of his men were tried and convicted, but Subianto never faced trial.

He never commented on these accusations, but went into self-imposed exile in Jordan in 1998.

A number of former democracy activists have joined his campaign. Budiman Sudjatmiko, a politician who was a democracy activist in 1998, said that reconciliation is necessary to move forward. Sudjatmiko left the governing Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle to join Subianto's campaign team.

Sudjatmiko said that international focus on Subianto's human rights record was overblown. "Developed countries don’t like leaders from developing countries who are brave, firm and strategic,” he said.

Subianto returned from Jordan in 2008, and helped to found the Gerinda Party. He ran for the presidency twice, losing to Widodo both times. He refused to acknowledge the results at first, but accepted Widodo’s offer of the defense minister position in 2019, in a bid for unity.

In the most recent election, Subianto has respected the democratic process.

He has vowed to continue Widodo’s economic development plans, which capitalized on Indonesia’s abundant nickel, coal, oil and gas reserves and led Southeast Asia’s biggest economy through a decade of rapid growth and modernization that vastly expanded the country’s networks of roads and railways.

That includes includes the $30 billion project to build a new capitol city called Nusantara. A report by a coalition of NGOs claimed that Subianto’s family would profit from the Nusantata project, thanks to land and mining interests the family holds on East Kalimantan, the site of the new city. A member of the family denied the report's allegations.

Subianto and his family also have business ties to Indonesia’s palm oil, coal and gas, mining, agriculture and fishery industries.

Subianto bristles at international criticism over human rights and other topics, but he’s expected to keep the country’s pragmatic approach to power politics. Under Widodo, Indonesia has strengthened defense ties with the U.S. while courting Chinese investment.

“Countries like us, countries as big as us, countries as rich as us, are always envied by other powers,” Subianto said during his victory speech after the election. “Therefore, we must be united. United and harmonious.”

The former rivals became tacit allies: Indonesian presidents don't typically endorse candidates, but Subianto chose Widodo’s son, 36-year-old Surakarta Mayor Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his vice presidential running mate, and Widodo coyly favored Subianto over the candidate of his own former party.

Raka is below the statutory minimum age of 40, but was allowed to run under an exception created by the Constitutional Court — then headed by Widodo’s brother-in-law — allowing current and former regional governors to run at age 35.

“This is the first time in Indonesian history that a sitting president has a relative who won in a presidential election,” said Yoes Kenawas, a research fellow at Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta. ”It could be said that the Jokowi political dynasty has been established at the highest level of Indonesian government."

Subianto has also had close ties with hard-line Islamists, whom he used to undermine his opponents.

But for the 2024 election, Subianto projected a softer image that has resonated with Indonesia’s large youth population, including videos of him dancing on stage and ads showing digital anime-like renderings of him roller-skating through Jakarta's streets.

“We will be the president and vice president and government for all Indonesian people,” said Subianto during his victory speech. “I will lead, with Gibran (to) protect and defend all Indonesian people, whatever tribe, whatever ethnic group, whatever race, religion, whatever social background. It will be our responsibility for all Indonesian people to safeguard their interests.”

Indonesia's likely new president haunts father of missing activist

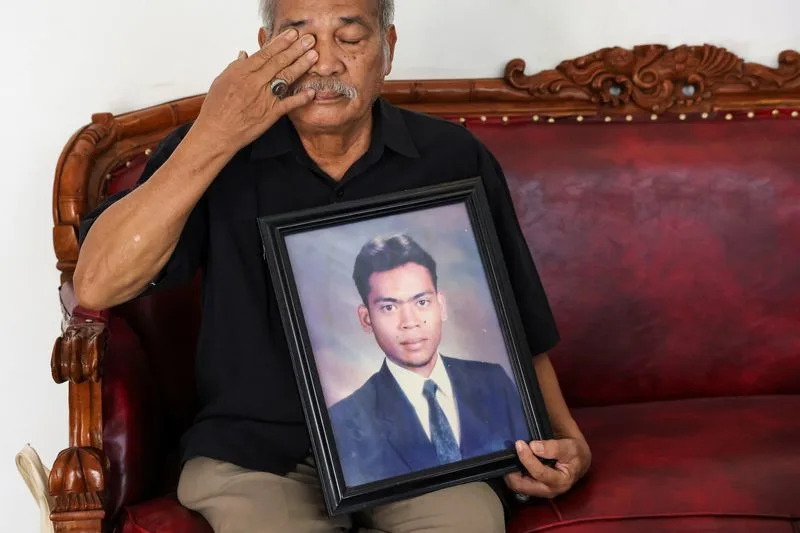

Paian Siahaan, the 77-year-old father of Ucok Munandar Siahaan reacts during an interview at his house in Depok on the outskirts of Jakarta.

Supporters of Indonesia's Prabowo Subianto are celebrating his likely ascent to the presidency, but for Paian Siahaan it is a painful reminder of his missing son and the man he blames for his disappearance in 1998.

Paian's 22-year-old son Ucok was one of the pro-democracy activists who disappeared during the chaotic riots of 1998 that precipitated the end of authoritarian leader Suharto's decades-long rule, at a time when Prabowo was an influential military commander.

A report by Indonesia's rights commission later indicated that Prabowo and several other soldiers were involved in kidnapping the activists, but Prabowo never went on trial, and has always denied any wrongdoing.

For nearly two decades, loved ones of alleged human rights abuse victims at that time have gathered every Thursday at the State Palace in Jakarta to join a silent protest to demand the government acknowledge and make amends for past atrocities.

The movement is known as 'Kamisan', derived from the Indonesian word for Thursday, its members say. Rights activists say it was inspired by mothers in Argentina, who staged silent protests every Thursday in memory of people who were killed or disappeared during the 1976-1983 military rule there.

Prabowo's win has come as a shock to those who attend the Kamisan gatherings, said Paian, 76, a frail, balding man with a grey moustache.

"We're stressed," he said, speaking in his home in West Java before leaving for Jakarta for the protest this week. "Will the case just disappear just because he's president? It's impossible... We had to cool down last night. There were mothers who cried."

Spokespersons for Prabowo did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

As Paian spoke, he held a framed photograph of his son, dressed in a jacket and tie. Other portraits of the young man were hanging on the wall of his drawing room.

Ucok's name remains on the electoral roll, and his father said this year too he received a letter from authorities asking him to vote on Wednesday, like he has for every election.

Unofficial quick counts from the election point to a sweeping victory for 72-year-old Prabowo, the current defence minister.

TOO YOUNG TO REMEMBER

Pre-election polls showed that more than 60% of Gen Z voters backed Prabowo, many of whom were likely too young to remember the events of 1998.

Prabowo was dismissed from the military that year amid the allegations of rights violations, including the kidnapping of 13 pro-democracy activists. He has always denied the claims and when pressed, has said all operations he conducted were legal.

Prabowo was banned from travelling to the U.S. for the alleged abuses, but the ban was lifted when he was named defence minister in 2019.

Ucok was in his early 20s, a budding economics student who joined the street protests over what he saw as then dictator Suharto's decades-long mismanagement of the country, his father said.

In the wake of Suharto's resignation, Paian said he and his family visited hospitals and police stations searching for his son.

After months they ended up at the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence where they met a dozen other parents also searching for their children.

Indonesia's human rights commission completed its report on the incident in 2006, which was submitted to authorities. But no action has been taken on its recommendation to set up a special human rights court to try those suspected in the disappearances in 1997-98.

Paian said he is still looking for answers about what happened to his son and what action will be taken against those responsible.

Aside from the 13 still missing, 9 others kidnapped in 1998 were eventually released, some joining Prabowo's party.

Figures like Budiman Sudjatmiko, one of the most vocal student critics of the Suharto regime, and who was kidnapped in 1996, has since joined the ex-commander.

Budiman now describes Prabowo as a "visionary" and says he supports him because "people change".

For Paian though, little has changed.

"I'm more worried now that he's won, but what else can we do, we keep each other strong," he said, "We feel afraid, but I'm fighting for my son."

Families of Indonesian activists tortured by soldiers 25 years ago shocked at general's election win

Activists holds yellow cards to symbolize a warning for President Joko Widodo who faces mounting criticism over his lack of neutrality in the Feb. 14 presidential election after he threw his support behind frontrunner Prabowo Subianto, a former general linked to past human rights abuses who has picked Widodo's son as his running mate, during 'Kamisan', a weekly protest held by the relatives of the victims of human rights violations in Indonesia, outside the presidential palace in Jakarta, Thursday, Feb. 15, 2024.

Families of Indonesian activists who were kidnapped and tortured by the military 25 years ago demanded justice in a protest Thursday and expressed shock over the apparent presidential victory of Prabowo Subianto, whom they blamed for the atrocities.

Currently the defense minister under outgoing President Jokowi Widodo, Subianto claimed victory in the presidential election on Wednesday, based on unofficial tallies showing he won by a big margin.

Subianto, 72, was a top general and commander of the army’s special forces, called Kopassus. They were blamed for human rights abuses including the torture of 22 activists who had opposed Suharto, the authoritarian leader whose 1998 downfall amid massive protests restored democracy in Indonesia.

Standing in a downpour outside the presidential palace in the capital, Jakarta, relatives of the activists held posters with pictures of the generals they held responsible for the 1998 disappearances. One of the pictures showed Subianto.

“Mr. Prabowo, if you are going to be the president, please resolve the enforced disappearance cases so that we, the victims’ families, can have peace,” Paian Siahaan, 77, told The Associated Press.

His son, Munandar Siahaan, was one of the activists who were assaulted by soldiers as Suharto’s authoritarian rule collapsed. Munandar Siahaan and 12 others remain missing.

Another protester, Maria Catarina Sumarsih, 71, said her son was shot by security forces in 1998 in a university campus. She read a letter addressed to Widodo that condemned Subianto's election victory. His running mate, a vice presidential candidate, is Widodo's eldest son.

Subianto expectedly avoided human rights issues in his campaign and benefitted from many voters’ focus on his promise to continue Widodo’s economic roadmap, Adhi Primarizki of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, a think tank in Jakarta, said.

“Unfortunately, human rights issues are not a popular issue in this election,” Primarizki said. Many voters were too young to witness human rights abuses in the Suharto era.