Evergrande, the embattled Chinese real estate giant with debts of $300 billion, has just been ordered to liquidate by a court in Hong Kong. What effect will this have, both within China and across the global economy?

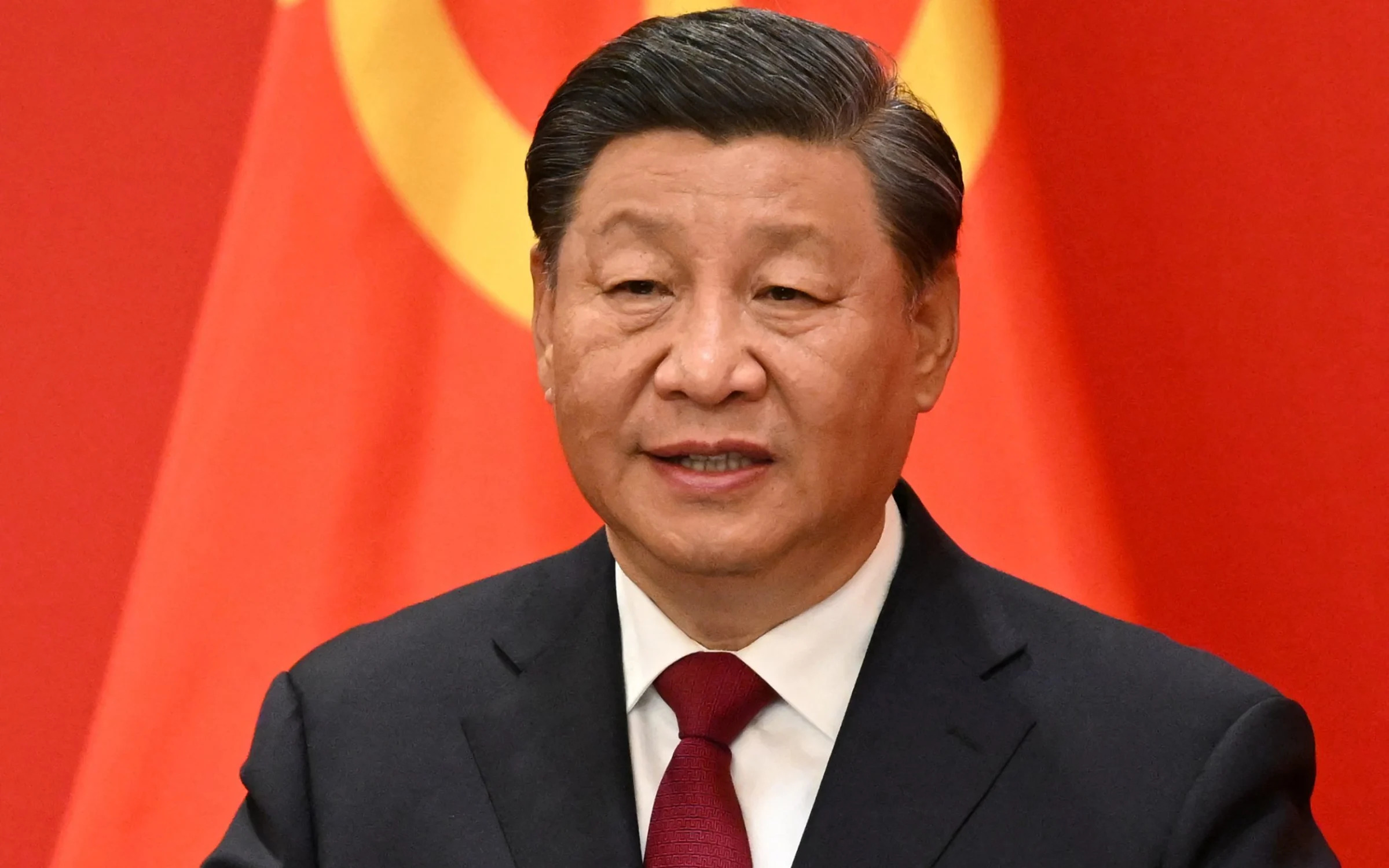

President Xi.

This latest twist is no surprise. Evergrande has long been dead in the water. The point to grasp is that Evergrande’s latest setback will not trigger a financial crisis in China; it is rather the result of the financial crisis which has been deepening for at least four years.

For far too long, up to 30 per cent of the Chinese economy had depended on a grossly inflated domestic property bubble. By 2020, when the government finally took urgent measures to limit this debt, its corrosive effects had distorted and disabled both the formal banking sector and also the much less accountable and manageable Shadow Banking system. Both are now in serious disarray as a result.

Ramifications of this unregulated borrowing and lending crisis have spread across the economy at large. The collapse of the property and construction bubble has weakened domestic economic confidence, deepening the unemployment crisis and posing major challenges to local government budgets. These domestic concerns have led to the current implosion of the Chinese stock market. In turn this has compelled foreign investors to take a more realistic position on China risk than believing the golden goose fables still being peddled by Beijing. Meanwhile, with some notable exceptions such as EVs, contraction of markets abroad for Chinese products has highlighted how much China remains export-dependent in a cooling global economy.

All of this calls into question the capacity of the Chinese leadership to halt and reverse the decline of the wider economy. Western commentators have been saying for years that China still has significant potential to revitalise its stagnant economy. Provided swift and deep-rooted reform policies are driven through, China could still pull itself out of the current downward spiral.

But this prospect is rapidly vanishing. The piecemeal efforts Beijing has made to prop up failing property giants like Evergrande and their backers, including the likes of Zhongzhi and Wanxiang, have had no fundamental impact. The CCP needs to devolve more economic powers to the private sector, and reverse the trend to ever-tightening centralisation. Yet Xi Jinping, seemingly unable to relinquish the self-defeating Marxist-Leninist ideology of strengthened Party and personal control, has abandoned the former and doubled down on the latter.

Evergrande had effectively defaulted by late 2021. It lost around 66.3 billion that year. Its founder sold $343 million of shares that November. Losses in 2022 were around 14.6 billion. Complex efforts since to manage debt down have all failed, which is reflected in Monday’s Hong Kong ruling. Evergrande’s operation in the US applied for bankruptcy in August last year. The chances are minimal that Evergrande creditors, whether in China or abroad, will see any of their money back.

The Hong Kong ruling may not in itself deliver the death-blow to Evergrande; the chances of full PRC co-operation in the process of liquidation in mainland China are slim. Some other formula will probably be adopted to disperse its toxic fragments more discreetly. But this too symbolises the issue of credibility the CCP is facing. Beijing remains astride the obsolete economic tiger on which Party power and authority has long depended. Now the tiger’s days are plainly numbered, the Chinese leadership still lacks both the vision and courage to dismount.

But the risks of clinging to this misguided orthodoxy are growing. The new generation of Chinese workers, who should drive forward the revival of their nation, no longer enjoys the growth which brought their parents out of poverty and into the now disintegrating housing market. Their inheritance has been frittered away buying millions of properties that will never be completed. Local government, in default of any more realistic strategy, has become largely dependent for its budgets on questionable land sales to developers who are now going under in their tens of thousands. Public resentment and disaffection with the CCP is on the rise. Xi and his henchmen, as yet safe in their Party citadel, may have fewer and fewer choices to make.

China Evergrande is ordered to liquidate, with over $300 billion in debt. Here's what that means.

A court in Hong Kong on Monday ordered China Evergrande to be liquidated in a decision that marks a milestone in China's efforts to resolve a crisis in its property industry that has rattled financial markets and dragged on the entire economy. Here's what happened and what it means, looking ahead.

WHAT IS CHINA EVERGRANDE?

Evergrande, founded in the mid-1990s by Hui Ka Yan (also known as Xu Jiayin), it is the world’s most deeply indebted developer with more than $300 billion in liabilities and $240 billion in assets. The company has operations sprawling other industries including electric vehicles and property services, with about 90% of its assets on the Chinese mainland.

WHY IS EVERGRANDE IN TROUBLE?

Hong Kong High Court Judge Linda Chan ordered the company to be liquidated because it is insolvent and unable to repay its debts. The ruling came 19 months after creditors petitioned the court for help and after last-minute talks on a restructuring plan failed. Evergrande is the best known of scores of developers that have defaulted on debts after Chinese regulators cracked down on excessive borrowing in the property industry in 2020. Unable to obtain financing, their vast obligations to creditors and customers became unsustainable. Hui has been detained in China since late September, adding to the company's woes.

WHY DOES EVERGRANDE'S PREDICAMENT MATTER?

The real estate sector accounts for more than a quarter of all business activity in China and the debt crisis has hamstrung the economy, squeezing all sorts of other industries including construction, materials, home furnishings and others. Falling housing prices have unnerved Chinese home owners, leaving them worse off and pinching their pennies. A drop in land sales to developers is starving local governments of tax and other revenues, causing their debt levels to rise. None of these developments are likely to reassure jittery investors. The health of China's huge economy, the world's second-largest, has an outsized impact on global financial markets and on demand for energy and manufactured goods.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

Much depends on the extent that courts and other authorities in the communist-ruled Chinese mainland respect the Hong Kong court's decision. The court is appointing liquidators who will be in charge of selling off Evergrande's assets to repay the money it owes. As is typical, only a fraction of the value of the debt is likely to be recovered. In the meantime, Evergrande has said it is focused on delivering apartments that it has promised to thousands of buyers but has not yet delivered.