The Many Dimensions of Consciousness. Why consciousness is so mysterious and hard to describe. Reviewed by Davia Sills

KEY POINTS-

- Consciousness is a complex phenomenon that people still cannot fully define or measure directly.

- Awareness and wakefulness/arousal are directly linked to consciousness but are not the same.

- Consciousness can be described along many dimensions.

- The common 2-D model (awareness and wakefulness) is useful but simplistic.

Awareness

What are you aware of right now? Is there any noise from the street outside? Maybe the smell of a nearby cup of coffee? Or perhaps the brightness of the screen on which you are reading this—or the ink and paper on which it is printed?

A key part of our human experience consists of being aware of the world around us, as well as being aware of our body and our mind: sensing when we are hungry or in pain, experiencing a range of emotions, and being aware of our own thoughts. We can ruminate and plan, solve problems, retrieve information, and nostalgically relive past experiences. Awareness is central to what we call consciousness, but—as we will see shortly—it is far from the only factor.

Lack of awareness is a strong indicator that someone is unconscious (that is why checking for responsiveness is one of the initial steps when administering first aid). Anesthesia renders a surgical patient unconscious because it removes awareness—both of the external world and, crucially, of any internal sensations, like pain. A less extreme case is drowsiness, which reduces awareness without eliminating it completely.

But here is the conundrum: There are many states where our awareness of our surroundings can be severely impaired while arguably still being highly conscious. An example is being in a state of flow, which means being completely absorbed in an engaging and enjoyable task. Many have reported flow states to be among the most meaningful experiences of their lives as well as being hyper-conscious even as external awareness becomes diminished. Research indicates that flow states reduce awareness (Sadlo, 2016) and that reduced self-awareness is a key aspect of entering into a flow state (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

Dreaming presents the opposite problem: We can be highly aware of dream experiences but lack many other aspects usually associated with consciousness when we sleep. We are rarely able to control what happens in our dreams but are simply carried along. Apart from lacking strategic control, even the ability to analyze what we are aware of seems impaired (things that seem to make perfect sense in dreams can seem utterly absurd when thinking about them later on in a wakeful state).

From this, we can see that awareness is not binary but moves along a spectrum from hyper-aware through drowsiness to completely unaware (e.g., under anesthesia). These examples also show that while consciousness and awareness are clearly related, they are not the same thing. Consciousness has many dimensions, and awareness is just one of them—a distinct phenomenon that is key to one specific aspect: conscious content.

Wakefulness and arousal

Awareness is difficult to assess from the outside, which is why in medical settings, wakefulness is often used as a measure of consciousness. A simple form of assessing wakefulness is to check if a person has the ability to open their eyes and have basic reflexes, like coughing and swallowing (National Health Service, 2022). While useful, this is a simplistic approach.

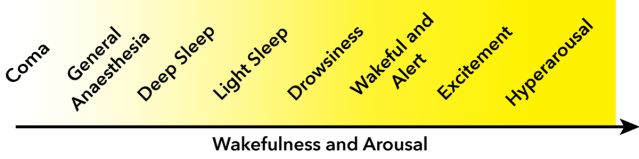

Wakefulness itself has many dimensions. A key one is arousal, which describes the level of alertness, attentiveness, and readiness for action (Lecea et al., 2012). In essence, arousal describes how ready our physiological and psychological systems are for action: an overall operational readiness. Just like awareness, arousal isn’t binary but comes on a spectrum of levels—from hyperarousal when we face danger to deep sleep, where systems take a while to boot up even after waking up (this is called sleep inertia).

A simplified model

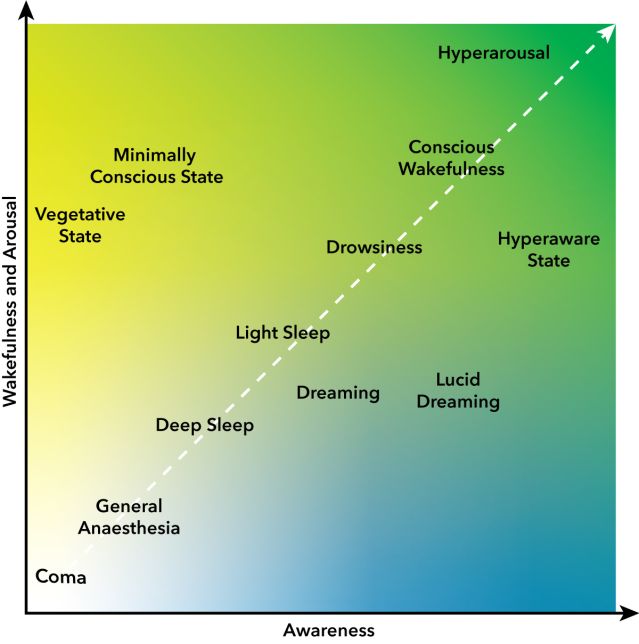

Using wakefulness and awareness, we can create a simplified model of consciousness that can be represented as a two-dimensional space. Most normally occurring events move along a diagonal line, meaning wakefulness and awareness increase or decrease roughly equally—like when we transition from conscious wakefulness through drowsiness into sleep. However, there are some states that don’t follow this rule. A good example is dreaming, where we have a high level of awareness but very low wakefulness.

Too simplistic? Many missing dimensions

This model can help us understand and categorize different conscious states and explain how consciousness is linked to but distinct from both awareness and wakefulness. However, this model grossly simplifies the many complexities involved in consciousness (Pang, 2023). Awareness is itself not a unidimensional entity. For example, when we’re absorbed in a task, we may be hyper-aware of everything to do with this task but may not notice anything else that is going on around us or within us (that’s why we can even forget to eat or not notice people entering the room). Conversely, being in pain can make us hyper-aware of a particular area in our body and not allow us to focus on a task.

In both cases, some aspects of awareness are exceptionally high, while others are not much different from someone who is asleep. Another missing aspect is the modality of awareness: A strong stench can make us suddenly become aware of our sense of smell, which we may have completely ignored up to that point. Even though we had no awareness of any smell prior to getting that bad whiff, this does not imply that we were unconscious or even any less conscious. Being conscious, then, clearly does not require awareness of all our senses. These are just a few examples, and this list could be extended much further and include wakefulness and arousal. The point is that this model is a helpful representation but not an accurate description of consciousness.

Conclusion

Consciousness is a complex and still largely mysterious concept that is incredibly hard to fully describe and measure. Awareness, wakefulness, and arousal all are directly related to consciousness but are themselves not the same as consciousness. There are states of consciousness that are marked by high awareness but low wakefulness and vice versa. Plotting those two dimensions on a graph serves as a useful illustration of consciousness as a two-dimensional construct. Although useful, this is a gross oversimplification of the many complexities and nuances involved and does not include the many more dimensions that make up this enigmatic thing we call consciousness

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Игры

- Gardening

- Health

- Главная

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Другое

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy