‘Beef’ Captures Our Beef With Religion and Western Therapy. Netflix’s series depicts religion that falls short of helping those in distress. Reviewed by Davia Sills

Marcella Locke (one of my research students at Seattle Pacific University; see bio below) and I were chitchatting during a research meeting, and we learned that we had both recently watched the critically acclaimed Netflix series, Beef. We thought it would be worthwhile to blog about our responses to this show, especially in relation to topics that we deeply care about in our research team—mental health, religion, and Asian American experiences. Below is a back-and-forth between Marcella and me.

Marcella

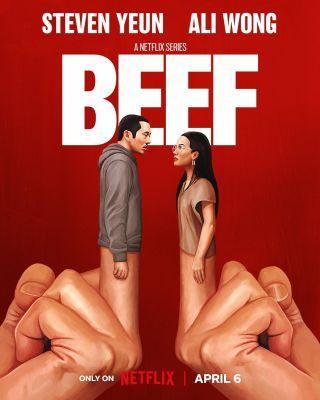

One of the most compelling and touching scenes in Beef is when Danny Cho, played by actor Steven Yeun, hesitantly enters the Korean American church as a last resort in hopes of finding solitude, comfort, and possibly a solution to his many life problems. As the congregation starts singing a worship song referencing hurt and brokenness, Danny tears up. He eventually breaks down crying intensely while simultaneously singing along to a song calling him to surrender all his problems to the Lord. Seeing this, the pastor comes over and speaks a prayer over Danny, asking God to be with Danny and show him unconditional love in his time of need.

This scene is a truly touching example of the healing potential of the church and accurately portrays the transformative Korean American church experience in many ways. But what struck me about this scene is the way the pastor approaches Danny’s brokenness. While I do not doubt that the pastor was well-intentioned, I couldn’t help but wonder: Is prayer all that the church has to offer for those who are struggling? It is evident that Danny is hurting and at rock bottom, yet all the pastor can offer is prayer. In other words, real conversations about what Danny is going through do not occur.

Me

I grew up in the Korean and Korean American churches. In a real sense, much of what I know of church culture is based on how Koreans and Korean Americans have practiced the institution of the Christian religion.

Like you, I found the church scene to be really powerful. Danny is entering of his own volition, sobbing uncontrollably; he is desperately seeking a solution to his numerous problems of living, or if no answers are forthcoming, at least an embracing community. In the language of psychotherapy, I would argue that he is in the preparation/determination phase of the Stages of Change Model (see Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), eager to make changes with the assistance of others, and taking that first step to check out resources. For Danny, the particular resource turns out to be the Korean church that he grew up in. He is ready for intervention with arms (or tear ducts) wide open.

On the first day of visiting the church, he even volunteers his professional services by fixing a hanging structure outside the church. It is a generous act that shows his desire for tangible aid in return, I would argue. But there is very little that the church can offer him outside of a few superficial Christian platitudes (like the prayer that you mentioned) and a comment from the pastor that the hanging sign that Danny just fixed for free is a bit crooked. The facial expression that Danny makes in response to the pastor’s comment sums up the mixed emotions that many who grew up in the Korean church can relate to: that feeling of being underwhelmed by the disconnect between the reality of the church and what it truly can and should be—a community that lives out the Biblical command “to look after orphans and widows in their distress” (James 1:27; New International Version).

Marcella

Yes, the church’s response was inadequate in that scene. Moreover, whenever conversations about mental health do occur in religious communities, it is not uncommon for church communities to characterize mental health problems as intertwined with one’s faith. From personal experience, I’ve commonly seen mental health problems viewed as personal religious failings. If a believer is suffering from depression, for example, then it must mean that they are weak, lack devotion, are a “bad” Christian, or are somehow being punished for their sins.

Growing up Catholic, I have seen many similar but subtle religious conceptualizations of mental health. For example, in a sermon speaking to parishioners who may be worried or struggling, the priest directed them to give all their anxieties to God. Sometimes Bible verses like Philippians 4:6 might be eagerly quoted: “Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God” (New International Version). This “surrender your mental illness to God” mentality can create a false narrative that all mental illnesses can be healed via religious means. Additionally, I commonly see mental health resources, like support groups and affordable mental health resources, advertised in monthly bulletins, but mental health topics are rarely discussed in sermons or otherwise in a real sense—they’re only talked about in relation to one’s religious commitment. Not only does this send the message that mental illness should not be talked about in church, but it also perpetuates mental health stigma and forces individuals to suffer silently.

While many church-goers, and research findings, can attest to positive ways that the church has facilitated their psychological well-being (e.g., religion buffers the effects of depression and increases life satisfaction; Lee, 2007), religious conceptualizations of mental health can cause a great deal of damage in Christian communities. Nonetheless, I believe that Christian communities, and churches in particular, are called to not only accurately speak about mental health and illnesses but guide their congregation to appropriate mental health resources. Church leaders should take concrete steps to destigmatize mental health in church communities by educating the congregation on mental illness (being careful not to stigmatize it in the process), distinguishing spiritual problems from mental health problems, making referrals to mental health providers when necessary, and ultimately, welcoming and accepting individuals despite their mental health problems. For more information on these solutions, please see the American Psychiatric Association Foundation’s “Mental Health: A Guide for Faith Leaders” (2018).

Me

Pivoting to Asian Americans and mental health, another scene that stood out was a direct quote, uttered in disgust, by Danny to his counterpart, Amy (Ali Wong): “You’re proof that Western therapy doesn’t work on Eastern minds.”

Some have quoted this insult to argue that, essentially, Beef depicts how truly lasting changes must come from things outside of professional therapy (e.g., Qualey, 2023). Others have taken on a defensive stance, asserting that it is dangerous to imply that psychotherapy does not work and bravely sharing about how they themselves have benefited from counseling (e.g., Yang, 2023). Both takes are persuasive and necessary to advance the mental health of Asians and Asian Americans, and I am glad they are out there.

My stance about the particular line from Danny is slightly, but importantly, different: The statement should also be received as an imperative to make professional counseling more compatible with Asian and Asian American worldviews.

In my own research, Asian Americans who adhere to more traditional Asian cultural values (e.g., emphasis on emotional restraint) are more likely to hold negative beliefs about seeking professional psychotherapy (Kim et al., 2016). Another example of seeming unsuitability is the emphasis on avoiding loss of face and how that might influence one’s decision to seek psychological help (Leong et al., 2011). Going deeper, how the causes of mental illnesses are articulated might impact things like one’s willingness to see a professional counselor (Kim & Kendall, 2015).

Marcella

It's important to make Western therapy more culturally compatible, especially with Asian worldviews, and I agree that the “problem” with Western therapy that Danny is alluding to lies in the fact that psychotherapy was created in a Western, individualistic context. Your points also remind me of an in-class conversation about the experience of psychotherapy across cultures; if an individual is not socialized to outwardly express their emotions, it may be uncomfortable and internally conflicting to openly express their emotions to a stranger, especially in a one-on-one setting. Therefore, it is important to recognize this disconnect as another potential barrier to seeking professional help and its effectiveness among Asians and Asian Americans.

Taken together, these barriers to mental health for Asian Americans simultaneously point to some practical solutions for making psychotherapy more congruent for the “Eastern mind” (e.g., less emphasis on emotional exploration and more sensitivity to interpersonal shame).

Co-author bio: Marcella A. Locke is a senior studying Developmental Psychology at Seattle Pacific University. Her research interests include how cultural and developmental processes interact and influence different psychological processes. After graduation, she is planning on pursuing a career in Speech-Language Pathology.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy