Vagus Nerve Activity and Social Sensitivity. Can flexibility in vagus nerve activity serve as a marker for social skill?

KEY POINTS-

- Differences in vagus nerve activity have been linked to emotional responses.

- Individual differences in HRV may mark differences in social sensitivity.

- This may have implications for clinical and developmental assessment.

Social situations can be very stressful, and we all vary in our “social sensitivity” or our ability to understand the feelings of other people and how they may come to interact with us. Someone with high social sensitivity understands the ebb and flow of conversation, listening at the appropriate time, and talking when it is their turn. Someone with low social sensitivity might ignore the rules, talk over other people, and ignore the social signals to stop talking. The better we understand these rules, the easier our social interactions will be. It turns out that at least part of our social sensitivity can be linked to one particular cranial nerve that helps the brain and the peripheral nervous system communicate.

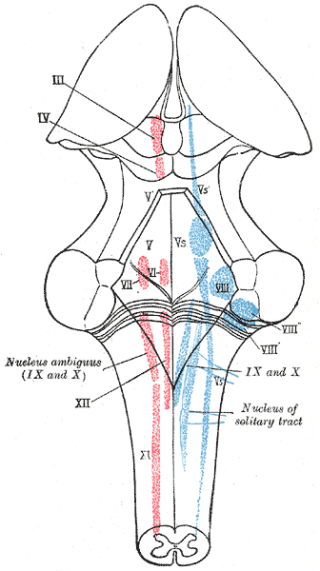

We each have 12 cranial nerve pairs that carry messages from the brain to and from various places in the body. Their job is to relay information between the brain and the rest of the body, usually between the brain and regions of the head and neck—hence the term cranial nerves. The 10th cranial nerve is a bit different. Called the vagus nerve from the Latin for “wanderer,” it extends from the brain to the heart and gut, allowing the brain and the organs in the chest and abdomen to communicate with one another. Among other things, the vagus nerve is essential in the proper function of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, responsible for the famous “fight or flight” response to emergencies.

Suppose you have an important deadline looming in front of you. This is a stressor, and our physical responses are familiar to all of us. Heart rate and respiration increase, blood pressure goes up, muscles tense up, and we may start to sweat. This is due to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. We are gearing up to “fight” or “flee” from that stressor. Once that stressor goes away, the parasympathetic system takes over and restores calm and balance in our bodies; heart rate slows back down, respirations decrease, our muscles relax, etc. The vagus nerve inhibits the activity of the sympathetic system, slowing down the heart rate when it is appropriate, and acting somewhat like a brake in a car. An increase in activity of the vagus nerve leads to decreases in heart rate, and a calm state. Decreases in vagus nerve activity lead to increases in heart rate and blood pressure.

We need both reactions in our daily lives. During an emergency, activity in the vagus nerve is decreased, allowing heart rate to go up in order to meet the demands of the emergency. Once the emergency is handled, we need to be able to calm back down, and activity in the vagus nerve increases. Being able to rapidly regulate the application of the vagus nerve “brake” is a marker of adaptive flexibility in our emotional response. More flexibility and a faster shift in vagus nerve activity mean a more adaptive emotional response.

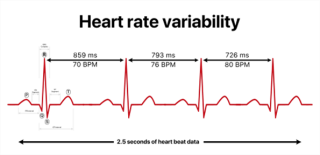

Researchers studying emotional responses refer to “vagal tone” or activity in the vagus nerve when we are at rest and calm, and “vagal flexibility” or the ability to control and change the response of the vagus nerve to the heart to meet the demands of whatever emergency we encounter. We all differ in vagal tone and flexibility. There is a non-invasive method for measuring both vagal tone and flexibility that can be obtained with a standard EEG setup. The activity of the vagus nerve can be seen in an EEG because of something called respiratory sinus arrhythmia, or RSA. When we inhale, activity in the vagus nerve increases and our heart rate slows down. During exhalation, vagal activity decreases and heart rate speeds back up again. This creates a perfectly normal variability in the time between heartbeats (called HRV or heart rate variability), measurable in the EEG.

Muthadie, Akinola, Koslov, and Mendes (2015) wondered if vagal flexibility might predict something about our emotional reactions to being in a social situation. They hypothesized that people with greater vagal flexibility (indicated by greater decreases in RSA during a demanding task) would show more social sensitivity in a social situation.

Using several different cognitive tasks made social by requiring work with a partner (like playing 20 questions) the researchers obtained EEG records both before and during the tasks, and paper-and-pencil measures of stress, depression, and loneliness. They also asked participants to take the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task,” which requires looking at a photo of only the eyes of a person and describing what that person is thinking or feeling. In the final study, they asked participants to take part in a hypothetical job interview and then receive and react to feedback on their performance—a very stressful social task.

They found that larger vagal flexibility was associated with less loneliness and that greater vagal flexibility was seen in people who were most accurate in detecting the thoughts and feelings of another with very limited information—i.e., higher social sensitivity. High vagal flexibility was also associated with less sociable behavior when participants received negative feedback on their job interview performance, and more sociable behavior when the feedback was positive. It all indicates that greater vagal flexibility tended to be paired with increased social sensitivity. This result may have implications for clinical and developmental assessment.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy