KEY POINTS-

- Dehumanizing the opposition and inflating one’s own ego and group identification creates endless battle.

- For reconstruction and repair, we need mindfulness, compassion, relationship, creativity, and insight.

- Relational cultural theory tells us that suffering is a crisis in connection, and the opposite is belonging.

.jpg?itok=W4wCeXly)

During the war in Vietnam, Venerable Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh was asked if he was from the North or South. He replied, half in jest but wholly earnest, “I am from the middle.” He actually was from the middle, the city of Huế, but he was also emphasizing his third way of nonviolence and peacemaking, far different from either opposing faction.

As a psychiatrist, humanitarian, and compassion educator, I’m thinking of Zen Master Hạnh these days, as the conflict between factions of Israelis and Palestinians rages on. Is there a middle? Could clarity arise that only a two-state solution, or some other mutually agreed upon solution, would be acceptable to the community of nations? Or are we doomed to the dangerous dialogue of abusive extremists on both sides?

The world has been held metaphorically hostage by this conflict in ways reminiscent of 9/11 during my lifetime, and the events leading up to World Wars I and II for older and past generations. The conflict is demanding our time and attention. In fact, conflict in the Middle East always evokes religious tropes such as Armageddon and the “end times,” calling in religiosity, spirituality, and psychoanalysis. I’m no expert on the former two, but I think even the latter one has largely failed us. We need something new.

Psychoanalytic Explanations of the Conflict

I have heard many psychoanalytic explanations of the conflict, some trauma-informed, and some frankly grandiose and ungrounded in their own way, with grains of truth stretched into vast fields of unresolvable misery. At their base and best, they point out that dehumanizing the opposition and autocratically inflating one’s own ego, group identification, and position creates endless battle or endless stalemate, with hopes of some ugly “ultimate victory” involving the annihilation of the opposition.

But analysis is far better at deconstruction than reconstruction and repair. For those, we need mindfulness, compassion, relationship, creativity, and insight, what I call “these five things.” Analysis has long stymied the process of repair with techniques of aloof commentary, pathologizing their “patients” or society-writ-large, and abstinence, neutrality, or withholding in terms of empathy. This has left many in the analytic community and their patients disconnected from shared humanity and mutual vulnerability. It furthers the trope that the analysand must essentially flounder with the analyst staying distant and avoidant of engaged, benevolent, and transformative human relatedness. The analysand must realize their basic needs were not always met by their human and imperfect mother, and cannot be met by the greater world. “Accept this version of your humanity,” this form of analysis seems to suggest, “and you will be freed from the delusion of repair, and be content in grief and mourning.” And, by the way, exalt the self-proclaimed power of the analyst.

I know I’m stereotyping analysts to a fault, but this is based on significant experience with many professionals and the dogma I’ve seen. Some young trainees claim that analytic training is now steeped in “relational theory,” which also seems to fall short of actually relating to your patients, in my view.

But analysis is having a mini-boomlet right now, with many psychiatrists and therapeutic trainees gulled into training programs believing it holds the intellectual high ground, without reckoning with its shortcomings on the heart-ground.

Relational Cultural Theory

Relational cultural theory, on the other hand, offers hope. It tells us that suffering is a crisis in connection, and the opposite of suffering is belonging. This view centralizes repair, relatedness, love, and compassion as the prime healing factors in all suffering. Analysis seems to hedge its bets on human relatedness and, thereby, becomes fascinated with a quagmire of so-called “primitive” defenses.

I believe what is happening in Israel and Gaza is a prime example of the mind/heart of humanity in anguish and at risk. This calls in the therapeutic community to see their work and the world with fresh eyes and engage in ways they had perhaps previously avoided.

Freud wrote that the unconscious can only be known "after it has undergone transformation or translation into something conscious." As I have written,

Perhaps what we are most painfully unconscious of is our very relatedness. Our relatedness has not been brought into anything approaching ease. Instead, it is a source of conflict—joy and torment, safety and anguish, war and peace. We are also unconscious of how our distresses are connected, and communicate, without our awareness or consent.

We see in real-time how our distresses are connected and communicate, without our awareness or consent. We see how unconscious, avoidant, and antagonistic we are of our deeper human relatedness.

What is happening in the Middle East is affecting people around the world, and it is affecting the therapeutic community. Domestically, the New York Times and other major media outlets have published articles about the Israel-Hamas conflict affecting these groups in the United States: Palestinian Americans, Muslim and Arab Americans, students, campuses, progressive Jews, and literary organizations, to name a few. So far, I’ve seen no articles exploring the impact on psychotherapy.

There are clear examples here of how we are metaphorically held hostage by world events, by our sympathies, and by our direct and indirect connections to peoples in conflict abroad. This is a long-running story of our multicultural, pluralistic democracy—but risks autocratic responses that will damage us all.

Here’s my relationally and trauma-informed analysis of what’s happening both in the Middle East and in the United States:

- Escalation and risk: The situation is escalated in hopes of gaining further attention from observers who are on the sidelines. The challenge is that the escalation will create cause for narrative, identity, and affective capture for those observers, to the detriment of the situation at hand.

- Narrative capture: The story of all-or-nothing, zero-sum, us-versus-them conflict becomes more powerful than the story of shared humanity, compassion, and creative, trauma-informed response.

- Identity capture: A militaristic or militant posture is taken at the expense of other identities, ostensibly in support of those deemed at greatest risk, but unempathically avoiding the risk one’s posture places on the sensibility or reality of others.

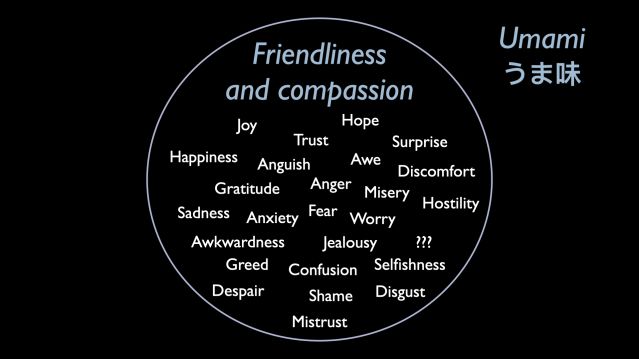

- Affective capture: Powerful emotions take hold at the expense of other, quieter emotions. All emotions are valid, but we have to ask: Why are we not able to hear the quiet voices in times of fear and threat? Why are we not able to allow these emotions to have a dialogue, perhaps informed by a touch of “umami”—the extra flavor of friendliness and compassion that makes our inner life and relatedness more tasty and delicious?

- The challenging identity experiences at the heart of it all: Why are we giving our vulnerable identities arms, instead of compassion and relatedness? Why isn’t there a Marshall Plan to address global, transhistoric, and intergenerational trauma, instead of perpetuating it?

The only hope for our world on the brink of broadened war and conflict is that the narrative of shared humanity, compassion, and Dr. King’s “creative maladjustment” takes root—that our affects and identities deepen and ripen into the “beloved community.” This requires those who are on the brinks to act judiciously, or as I put it in my previous post, “with cool heads and warm hearts.”

Zen Master Hạnh also said, “When the crowded Vietnamese refugee boats met with storms or pirates, if everyone panicked, all would be lost. But if even one person on the boat stayed calm and steady, it was enough. They showed the way for everyone to survive.”

The more we support our cool, calm, and steady heads, the more we cultivate our warm hearts, the greater the likelihood we will all survive this conflict, and perhaps even resolve it.