KEY POINTS-

- Brief, potent mindful tactics are handy stress busters and are easily taught and entrained.

- Visualization takes the basic tactic of observing the moment and introducing a setting or event to "sit with."

- Perceiving body, heart, and thoughts in calming situations allows for self-mediated stress reduction.

- Visualization can also be used as "rehearsal" prior to stressful situations—to identify and adapt to.

"To freak out—perchance to dream. Ay, there’s the relief!" — Anon

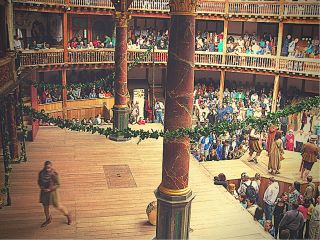

For this third of the "core four" brief but potent meditation-based tactics, we can take a tangential cue from the legendary playwright and, as it turns out, early stress management pioneer Mr. William Shakespeare. While the Bard was waxing on about dreamy end-of-life issues, we can use that imaginal experience, in this case, the universal phenomenon of daydreaming, as a tactic in managing anticipatory anxiety and tension through mindful visualization and intentional rehearsal.

A quick stage-setter... these four "mighty mini mindful moves" are drawn from a new book project (Mindfulness in Medicine, Springer, out early 2024) that addresses incorporating mindfulness content and practices throughout the whole of today's complex, stressed-out healthcare system. These mighty minis are easily taught and entrained stress-busters, ultimately meant to become our second-nature responses to stressful moments, whether in a medical setting or elsewhere.

While a regular ol' daydream is usually a spontaneous occurrence happening in the midst of boredom or a lack of engagement in social interaction, in this situation, the aim is an intentional practice of manufacturing a narrative in the midst of a brief meditation session. To be more specific, we incorporate a scene or story into a short meditative sequence and "sit" briefly with what bubbles up in body, heart, thought, and attention or awareness with that manufactured script in experience.

These tactics have wide application in professional practice, as in the guided sequences in hypno-therapeutic exercises such as EMDR and "brainspotting." Imaginal Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) is another adjacent application for this practice, which has also shown great benefit in veteran populations to address flashbacks and night terrors associated with PTSD. In that flavor, we can, in essence "write a better ending" to the script of a recurrent nightmare or terror in conscious thought before bed. It often softens the somatic or emotional aspect of those awful experiences, with the REM-behavior "soundtrack" becoming less pronounced and the dreamscape more observed than immersed in.

Here, we're applying the basic activity for home use. We'll cover this in two acts. And we need not forfeit a pound of flesh to learn, teach, or use these, forsooth.

Act I: A "Balm of Hurt Minds" (Macbeth)

OK, this quote snippet was referring to sleep, not meditation, but the soothing goal is the same. This tactic is most recognized and employed in an admittedly comic-cliché, "go to my happy place" way. For example, the well-known tactic of sequential tensing and relaxing of muscle groups in Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR, for you acronym lovers) can be boosted with some parallel storytelling. With each muscle group tightening and then releasing, we can pair it (in our own imagination or via some guided audio) with, say, the sun coming up a little higher as we lie on a beach in Bali or the steam and water getting incrementally more cozy in a lux spa retreat.

We can use our basic meditative recipe here (you know... settle, watch, lose the watching, regain it without too much fuss) without the flexing. In this exercise, we do apply a little more intentional, observational rigor than in informal daydreaming. Footlights, please:

- First, choose our setting or scene of choice, whether of nature, comfort, in the presence of a loving other, or even a spiritually nourishing entity, if that is what is preferred.

- We warm up with some brief breath observation work—just a few breaths may be enough, as it's a "mini," after all.

- We then introduce a soothing setting of choice and "sit with it." The introduced settings in this style are purposely calming—walking in the woods, lying on that beach, sitting in Nana's kitchen as cookies are being baked—as a therapeutic juicing of some historically pleasant or comforting memories.

- An emphasis here is on taking a granular snapshot of the effect of that imagined setting—sensory, emotional, thoughts. We sample a quick immersion in that happy place, attending to its imagined delights.

- Then, a breath or two back to the "mind's eye," watcher's experience. We let that immersion's effect soak in and note any sense of calm, any reduction in tension. And, scene.

While the expectation is for stress reduction (that's what the setup is for, after all), there is certainly the possibility of intrusion of stressful phenomena from "outside the theatre," so to speak. As with any meditative exercise, it's worth attending to that, identifying it, then resetting with the practice scene in mind and giving it another go or two.

We may work with our patients/students/selves over time and use trial-and-error to settle on a few favorites from direct memory or past practice to return to. (My greatest hits include a peaceful koi pond at a local park; sensory memories of a post-call early Sunday morning; freshly mown first tee on a golf course back in internship; and singing a midnight lullaby to my youngest, just a few days old.)

Act II: (Anticipate...) "The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune..." (Hamlet)

That same short template of an intentional setting in mind can be used to virtually rehearse some anticipated, likely difficult-to-hold phenomena that arise in some identifiable, stressful experiences. Visualization or rehearsal is an imaginal tactic that has been long effective in CBT, working with phobias and other discrete fears and states of dysphoria. As an example, we can use our guided imagination to mentally rehearse and gradually desensitize to a feared situation—such as driving over a bridge, attending a funeral, or taking an exam.

In the new book, we use medically-driven examples, such as submitting to a lab blood draw or prepping for tolerating the MRI with its air-raid and gnomes-with-hammers sensory display. Whether in a clinical or other stressful event, working on this with our patients/students/selves prior to direct exposure to the event can help reduce the "radioactivity" of the actual showtime, mitigating some of the novelty and immediacy that can amplify a sense of threat.

The "rehearsal" aspect of this expands the setting to a series of events to walk through in mind. It's not the same as being there, but in this preparatory rehearsal, we can at least acquaint ourselves with the probable features, thereby reducing the "bad surprise" aspect.

Let's use a familiar example... road rage. Curtain raises:

As with the other "soother" tactics, we start by briefly planning out the scene conceptually. We can divvy the sequenced "moments" into, say, three parts:

- The setting of pre-cutoff locomotion (imagine the smell of the car, the felt position in the seat, the motion and sound, the sad stray fry in the cup holder)

- The rude cutoff (in my book Practical Mindfulness, a concluding vignette involves an oblivious screamer into his cellphone as he swings his, say, Emasculade XL into my lane) perhaps anticipating a glare, snide comment, or horn blare (hopefully not worse) in response

- A resolution snapshot, with the tense moment passing, the neurochemical tsunami receding, and some effort to return to normal programming.

Again, with each step, we "picture" it in our mind and linger for a couple of breaths, tending to the imagined, felt sense of the moment in those realms (somatic, emotional, "thinky" ). We move to the next mini-scene, in this case, frame out in mind the moment of offense and immerse in the imagined radioactivity. Sit with it for each of the steps, including, importantly, the resolving moment.

Then, as with the other visualization, we take a breath or two back in the "mind's-eye" position. We take the sequence in and the resultant state. Et fini.

I have a couple of notes to end.

This is an essential caveat: visualizations are meant to be helpful in daily bumps, not for a headlong dive into some traumatic re-experiencing. While these steps may sound familiar to those practicing or engaging in EMDR, there is a reason those are professional-provided, guided experiences.

Also, one is to not give short shrift (or other shrifts, should they exist) to the "resolution" step of a sequenced visualization or rehearsal. Stressful events are often supercharged by the post-head-snapping, "How will I make it?" sense of open-ended tension without closure. Walking through a concluding return to a stable state rehearses the reality that even emotionally tough moments have an end. Obvious, yes, but a sharp feature of those bursts of stress is a momentary sense of "forever in pain," for which a reminder of its impermanence is a salve.

All's well that... you know.