KEY POINTS-

- Using "therapy-speak” can promote your self-interest over your partner's wishes.

- Learn to describe not characterize your partner's actions.

- Psychological theory and therapy risk promoting self-fulfillment over care and concern for others.

- Partners who see themselves as individuals and as a couple can negotiate collaboratively.

“The relationship was toxic. And her ex was such a narcissist! Yes, they were definitely co-dependent. She was totally triggered by the whole thing, but it probably had something to do with her anxious attachment style—she ignored the red flags. She was probably just projecting anyway.” 1

This is a tongue-in-cheek example of the “weaponization” of mental health terminology that is occurring in and about relationships.2

The Rise of “Therapy-Speak” in Relationships

“Therapy-speak” refers to the use of therapeutic language out of the context of therapy itself, which is getting a lot of attention for its use in relationships.3 Social media is now flooded with therapy-speak videos, posts, and memes, which results from the increasing accessibility to therapy in the digital age. We are encouraged to set boundaries, reject toxicity, and hold space.

Why is This Happening?

That the language of therapy is adopted by the public is not a new phenomenon. Hysteria, shell shock, and inner child are terms originating in psychoanalytic theory. Psychoanalysis also gave us holding space—the metaphoric space the mother provides the infant that allows the baby to develop its own identity.4

While the practice of using therapeutic concepts in our everyday social interactions is not new, digital social media not only amplifies the spread of therapy-speak, it also uses it differently. The current use of this language is focused more on relational dynamics than on individual neurosis.5

This expanded use of therapy-speak is causing concern as an indicator of a society that is “obsessed with self-actualization and personal fulfillment at the expense of concepts like duty, virtue, and collective obligation.6

Should We Be Looking Out for Number One?

This is the question Duke University Professors Michael and Lise Wallach posed in their 1983 book Psychology’s Sanction for Selfishness: The Error of Egoism in Theory and Therapy”. The Wallachs note that Maslow, for example, emphasized that self-actualizers are motivated by inner rather than outer determinants and are, therefore, free, self-determined, autonomous—their authentic self. Others in their world become a means to their self-actualization.7

In the years since the writing of this book, the language of psychological theory and therapy has become a sort of worldview.8 This worldview, filtered through the social media of self-help and self-care, which is too often expressed as satisfying one’s own needs, is a risky substitute for the goals of actual therapy.

The construct of need has a long history in the field of Psychology. It is the way that psychologists in the early 1900s incorporated the idea of self-interest, promoted by both the economic theory of Adam Smith and the evolutionary theory of Darwin, into the psychology of human motivation.

Over subsequent years, the psychological construct of need has become reified—it is no longer a theoretical construct about motivation, it is a concrete reality—I am entitled to have my self-identified needs met!

Here are the implications in our relationships of the reification of need as our primary motivation:

- Needs are demands we are entitled to have satisfied

- Needs are not negotiated, they are exchanged in quid pro quo arrangements

- Not having a need fulfilled is an injustice that builds resentment

- Partners value each other in terms of how well they fulfill each other's needs; others are a means to our own self-actualization

- Not having our needs fulfilled is justification for leaving a relationship

How Therapy-Speak Is Being Used in Relationships

The risk of therapy-speak is that it will be used as an enhanced version of the idea that our needs must be catered to. For example, in an internet discussion, a popular actor wanted his partner to honor his boundaries by not going out with people of whom he disapproved and by taking down pictures of herself that he deemed inappropriate. The writer of the article suggested that the actor was “…just advocating for his needs in the relationship?”9

The above actor needs his girlfriend to limit her actions. Perhaps she needs to go out with friends the actor does not like. When we are all self-actualizing, whose needs come first? His anxiety is triggered by what she does; she is co-dependent so complies because of her anxious attachment style. Perhaps the relationship will become toxic.

Let’s step back from this morass of therapy-speak. Let's talk about how couples interact without using therapy-speak. Therapy-speak is just the newest way to characterize rather than describe our partner’s actions.

Characterizing our partner’s action is giving our personal take on it. We do this all the time for the things we like about our partner and things we don’t like. However, we seldom describe an action our partner is taking that we do not like. For example, if my partner doesn’t pay attention to what I am saying, I might blurt out… "You are ignoring me!” I am characterizing his action when I label it as ignoring me. This is how it feels to me. It is not a description of what he is doing! The difference between describing an action and characterizing it is a big deal. When we describe an action, we stick to what is observable or factual.

Therapy-speak is a new and enhanced way of characterizing our partner's actions. It gives our characterization the cloak of objectivity; it lends professional credibility to how we view our partner and pathologizes his/her actions.

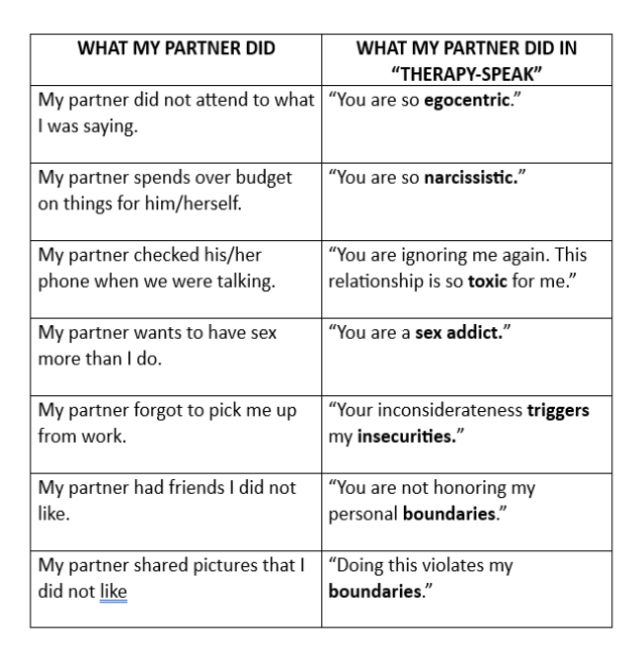

Here is a table that shows how to describe an action alongside characterizing the action in therapy-speak.

My partner will not see his/her action as I am characterizing it and he/she is likely to react negatively. Using therapy-speak absolutely will prevent the honest discussion of issues that always occur in relationships.

Eli Finkel and his associates tell us we are increasingly looking to fulfill our self-esteem, self-expression and self-actualization needs in our marriages.10 However, he also notes that marriages driven by needs for self-expression are “suffocating” us. Unfortunately, he never questions the idea that self-actualization itself may be the problem because of its focus on individual self-interest.

It is time to look beyond seeking our own self-actualization needs in our relationships. Fortunately, there is another way.

Collaborating in Relationships

A collaborative relationship11 is one that is defined by the following:

- It is a committed relationship that is not defined by gender.

- It is one in which partners see themselves simultaneously as individuals and as a couple.

- With this simultaneous perspective, the couple can negotiate collaboratively the things in life that allow them to flourish as individuals.

- The things that allow partners to flourish are not defined as needs to which they are entitled—the focus on self cannot be an entitlement.

Negotiating Collaboratively Is How to Manage Self-Interest and Concern for Your Partner

Whether you are making big plans, like where to live or career choices, dealing with day-to-day issues like who does what at home, or talking about ways of being intimate, there is a process you can follow to arrive at a resolution that considers what both of you want. Here are the steps in the process of negotiation:

- Thinking things through: Take time to think through what is important to you about the issue you want to talk about.

- Approaching your partner: Give your partner a heads up. They need time to think through what is important to them. Then set an appropriate time and place to talk.

- Expressing what you want: When you meet, you have the chance to express your views on the issue. Each of you wants to say what is important to you and why it is important to you. By expressing what you want and listening to your partner, you show that every concern of yours is a concern of mine. And, this is how you can get to know your partner better.

- Finding a collaborative solution: Work toward finding a solution that considers both partner’s wishes and wants. Collaboration is not cooperation. Collaboration is about the process of working together; cooperation is the result of working together. (I can cooperate with you by stepping aside while you do what you want.) Neither is collaboration about compromise, which frequently is the result of one of you capitulating.

Remember, collaborators are equals. They share authority and negotiate in good faith. Through collaborative negotiation, we can move into a new kind of relationship.

Therapy-Speak Will Be With Us

We are likely to continue to adopt the language of psychological theory and therapy. But we do not want to use it only to enhance our own self-interest. Let’s use it to enhance us as individuals and as couples simultaneously.