WISDOM- Are Attacks on Literature Signs of Cultural Decline? Personal Perspective: Are we in the throes of anti-intellectualism? Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

KEY POINTS-

- Are non-human technological forces reshaping the traditional role of literature in modern societies?

- Are attempts to cut literary studies detrimental to student cognitive growth?

- Are nations still measured by the quality of their literature as Emerson believed?

- What happens to the "soul" of a literary culture when it is replaced by non-human software programs?

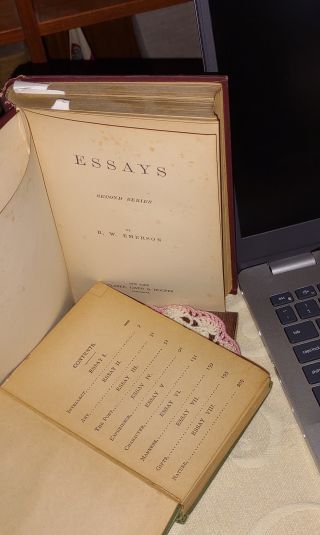

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) is not someone we hear much about today. Yet a strong case can be made that he is one of the most important figures in the development of our national literary culture. He might even be seen as the “father of our national literature”—at least until Mark Twain (1835-1910) came along and assumed that title with his emphasis on “voice” in all literary enterprises.

Emerson came on the scene at a time when America had not yet developed much of a literary tradition. James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), author of The Leatherstocking Tales, was lauded by some as America’s greatest novelist. However, his star diminished when it became obvious he was attempting to adapt shopworn historical romance genres to the American frontier. The fit just did not work.

Emerson recognized the dearth of a strong American literary tradition and set about trying to rectify our overly materialistic, often anti-intellectual cultural values. His basic premise was that a nation is not truly great until it has created lasting literature. In that context, Emerson saw that America was woefully lacking when compared to many other great nations throughout history.

In a series of essays, especially “The Poet” (1844), Emerson urged his fellow Americans to honor the importance of literature in every national culture—but especially the emerging American culture. He suggests that literature is the soul of a nation, for it permeates outward and shapes the way nations think, act, and perceive themselves. He also considered the possibility that America, as a new nation in its thrust to achieve greatness, might instead become embroiled in overly materialistic and even anti-intellectual pursuits. Still, he held out hope that America could produce great literature of, by, and for the common man. He eventually included women in those concerns.

Today, it could be argued that Emerson’s vision of the central role of literature in all great cultures has been severely eroded. Many K-12 schools no longer offer literature courses. Libraries and librarians are also under attack in many areas for displaying books that challenge the status quo. Books that encourage young people to pause and look at the world around them through a new lens are often banned and sometimes burned. Software programs have been created to imitate human artists, but without the soul of real literature. Meanwhile, real human authors struggle to keep their literary works from being exploited by others for profit. In the eyes of some, this is the ultimate triumph of materialism over the literary culture Emerson argued was so essential in the development of a great nation’s identity and values.

The world today is very different than the one Emerson wrote about. Yet it is clear from his essays that he would be deeply concerned by the subjugation of literary culture in our libraries, schools, and national discourse. He would undoubtedly have seen it as a sign of a great national decline rather than an advancement of cultural values.

Many of us who are fortunate enough to still teach literature see the unquenchable need students have for texts that are often denied them in their schools and homes. Emerson would have seen this as an unpardonable omission in the development of human intelligence and human values. In “The Poet,” he wrote, “Within the form of every creature is a force impelling it to ascend into a higher form.” Emerson believed literature and other forms of art, together with direct interactions with nature, provided the energy that sent human nature on this upward trajectory. Clearly, Emerson would have seen book banning, attacks on teachers and librarians, and other such activities as concessions to the darker impulses of anti-intellectualism in human nature.

For Emerson, a nation without a strong literary tradition is a nation in name only. It could never achieve real greatness. In many ways his predictions that American had the potential to create great literature came to fruition in the twentieth century. American literature rose above its humble beginnings of authors entrenched in the European literary tradition. We should not dismiss the contributions of Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Emily Dickinson, and other nineteenth-century writers who extended our earlier literary culture. However, in the early decades of the twentieth century our writers started to explore the diversity of American life as it existed in every part of the country. Later yet, we started to honor the literary contributions of Black Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic Americans, and others who broadened the range and appeal of our literature. The same is true of recent literature that explores the struggles and experiences of gay, transgender, and other marginalized groups that had often been excluded from literary expression. All of this would have met with Emerson’s wholehearted support.

Today, however, I believe he would see disturbing signs of a nation that is undermining the very literary culture that has helped to thrust it to greatness in spirit and deeds. I believe he would be very concerned—as we all should be.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Story/Motivational/Inspiring

- Technology

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness

- News

- Culture

- War machines and policy