ANGER-

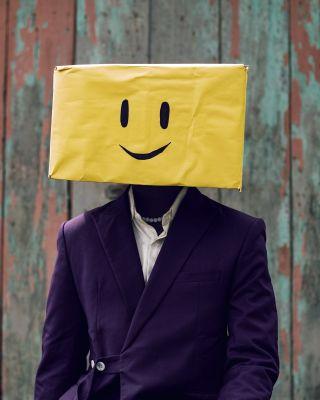

Smiling to Death: The Hidden Dangers of Being ‘Nice’

We can learn to bring more awareness to our own emotions and needs.

Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

KEY POINTS-

Pushing down anger, prioritizing duty, and trying not to disappoint others are leading causes of chronic illness.

Ignoring or suppressing how we feel and what we need revs up our stress response, pushing our body toward inflammation.

Our need to maintain membership in our groups leads us to suppress our emotions in a tug-of-war between attachment and authenticity.

Being nice and pleasing others—while socially applauded and generally acknowledged as positive traits—actually can harm our health, says Gabor Maté.

Decades of research point to the same conclusion: Pushing down our anger, prioritizing duty and the needs of others before our own, and trying not to disappoint others are leading causes of chronic illness, says the author of the New York Times bestseller, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture.

“Our physiology is inseparable from our social existence,” argues the Vancouver physician. Ignoring or suppressing how we feel and what we need—whether done consciously or unconsciously—revs up our stress response, pushing our body toward inflammation, at the cost of our immune system, he says.

“If we work our fingers to the bone, if we’re up all night serving our clients, if we’re always available, never taking time for ourselves, we’re rewarded financially and we’re rewarded with a lot of respect and admiration,” says Maté, “and we’re killing ourselves in the process.”

Personality Features of People With Chronic Illness

When Maté reviewed the research on the chronic illnesses he’d treated for more than 30 years, he discovered a pattern of personality features that most frequently present in people with chronic illness:

Automatic and compulsive concern for the emotional needs of others, while ignoring one’s own needs;

Rigid identification with social role, duty, and responsibility;

Overdriven, externally focused hyperresponsibility, based on the conviction that one must justify one’s existence by doing and giving;

Repression of healthy, self-protective anger; and

Harbouring and compulsively acting out two beliefs: I am responsible for how other people feel, and I must never disappoint anyone.

“Why these features and their striking prevalence in the personalities of chronically ill people are so often overlooked—or missed entirely,” is because they are among the “most normalized ways of being in this culture…largely by being regarded as admirable strengths rather than potential liabilities,” says Maté.

These characteristics have nothing to do with will or conscious choice, says Maté.

Coping Patterns

“No one wakes up in the morning and decides, ‘Today, I’ll put the needs of the whole world foremost, disregarding my own,’ or ‘I can’t wait to stuff down my anger and frustration and put on a happy face instead.’” Nor are we born with these traits—instead, they are coping patterns, adaptations to preserve our connection to others, sometimes at the expense of our very lives, he warns.

We develop these traits to be accepted, in what Maté describes as the tug-of-war between our competing needs for attachment and authenticity. We need attachment to survive, as we are a tribal species, wired for connection, conforming to the needs and rules of others to secure our membership in groups.

But we also need authenticity to keep us healthy. We’re designed to feel and act on emotions, especially the “negative” ones. It’s our alarm system to survive danger. Psychiatrist Randolph Nesse, founding director of the Centre for Evolution and Medicine at Arizona State University, explains that we’ve evolved to survive, not to be happy or calm.

Low mood, anger, shame, anxiety, guilt, grief—these are all helpful responses to help us meet the challenges of our specific environments. Having loud, sensitive protective functions like emotions that sound alarms when we’re threatened isn’t a design flaw. It’s a design success.

Our emotions act as smoke alarms to match the perceived threats around us, says Nesse. This seems most obvious with emotions, like fear, that scream out warnings of danger. But even more subtle emotional experiences help us navigate threats and rewards for survival. The discomfort of a low mood is signaling that there aren’t enough rewards in our environment to outweigh the risks of being there, motivating us to seek out circumstances that are more rewarding or conserve our energy in a safe place—like in bed bingeing Netflix—until the rewards return.

Anger, too, is a necessary response to fight inequities, violations, and having our needs blocked. It’s our most effective tool to mobilize action against injustice. The biggest obstacle to social justice is not heated opposition, but apathy. And, yet, society has socialized many of us to suppress anger. Even the vilified emotion of anger’s more subtle form, resentment, is helpful. When our body and brain pick up subtle cues that our boundaries are not being respected, the resentment alarm shouts out loud and clear to assert these boundaries before we even have time to reflect on the situation.

Suppressing Vital Emotions

Yet, the need to maintain membership in our groups has led us to suppress these vital emotional signals, disarming our ability to protect ourselves, says Maté. Even more problematic, says Maté, is that conscious suppression of emotions has been shown to heighten our stress response and lead to poor health outcomes. “We know that chronic stress, whatever its source, puts the nervous system on edge, distorts the hormonal apparatus, impairs immunity, promotes inflammation, and undermines physical and mental well-being,” says Maté. And numerous studies show that a body stuck in a chronic stress response stays in an inflamed state, Maté continues, the precursor of many chronic illnesses, such as heart disease, cancer, autoimmune diseases, Alzheimer’s, depression, and many others.

Maté is careful not to use this research to blame people for their own illnesses. “No person is their disease, and no one did it to themselves—not in any conscious, deliberate or culpable sense,” he says. “Disease is an outcome of generations of suffering, of social conditions, of cultural conditioning, of childhood trauma, of physiology bearing the brunt of peoples stresses and emotional histories, all interacting with the physical and psychological environment. It is often manifestations of ingrained personality traits, yes—but that personality is not who we are any more than are the illnesses to which it may predispose us.”

Our personality and coping styles reflect the needs of the larger social group in which we develop, says Maté. “The roles we are assigned or denied, how we fit into society or are excluded from it, and what the culture induces us to believe about ourselves, determine much about the health we enjoy or the diseases that plague us.” Illness and health are manifestations of our social macrocosm, he argues.

It’s no surprise, then, that the inequities of society deeply affect our health, with those more politically disempowered or economically disenfranchised being forced to shape and suppress their emotions and needs most gravely to survive, says Maté. This means systemic change to fight inequities and focus on social justice is the foundation of improving our health, a common thread in The Myth of Normal.

At the same time, we can work to unlearn these behaviour patterns by bringing more awareness to our own emotions, signals in our bodies, and our needs, rather than automatically ignoring them in the service of others.

“The personality is an adaptation,” says Maté. “What we call the personality is often a jumble of genuine traits and conditioned coping styles, including some that do not reflect our true self at all but rather the loss of it.”

Maté describes true healing as opening ourselves to the truths of our lives, past and present. “After enough noticing, actual opportunities for choice begin to appear before we betray our true wants and needs,” he says. “We might now find ourselves able to pause in the moment and say, ‘Hmm, I can tell I’m about to stuff down this feeling or thought—is that what I want to do? Is there another option?’

“The emergence of new choices in place of old, preprogrammed dynamics is a sure sign of our authentic selves coming back online.”

ANGER-

Smiling to Death: The Hidden Dangers of Being ‘Nice’

We can learn to bring more awareness to our own emotions and needs.

Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

KEY POINTS-

Pushing down anger, prioritizing duty, and trying not to disappoint others are leading causes of chronic illness.

Ignoring or suppressing how we feel and what we need revs up our stress response, pushing our body toward inflammation.

Our need to maintain membership in our groups leads us to suppress our emotions in a tug-of-war between attachment and authenticity.

Being nice and pleasing others—while socially applauded and generally acknowledged as positive traits—actually can harm our health, says Gabor Maté.

Decades of research point to the same conclusion: Pushing down our anger, prioritizing duty and the needs of others before our own, and trying not to disappoint others are leading causes of chronic illness, says the author of the New York Times bestseller, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture.

“Our physiology is inseparable from our social existence,” argues the Vancouver physician. Ignoring or suppressing how we feel and what we need—whether done consciously or unconsciously—revs up our stress response, pushing our body toward inflammation, at the cost of our immune system, he says.

“If we work our fingers to the bone, if we’re up all night serving our clients, if we’re always available, never taking time for ourselves, we’re rewarded financially and we’re rewarded with a lot of respect and admiration,” says Maté, “and we’re killing ourselves in the process.”

Personality Features of People With Chronic Illness

When Maté reviewed the research on the chronic illnesses he’d treated for more than 30 years, he discovered a pattern of personality features that most frequently present in people with chronic illness:

Automatic and compulsive concern for the emotional needs of others, while ignoring one’s own needs;

Rigid identification with social role, duty, and responsibility;

Overdriven, externally focused hyperresponsibility, based on the conviction that one must justify one’s existence by doing and giving;

Repression of healthy, self-protective anger; and

Harbouring and compulsively acting out two beliefs: I am responsible for how other people feel, and I must never disappoint anyone.

“Why these features and their striking prevalence in the personalities of chronically ill people are so often overlooked—or missed entirely,” is because they are among the “most normalized ways of being in this culture…largely by being regarded as admirable strengths rather than potential liabilities,” says Maté.

These characteristics have nothing to do with will or conscious choice, says Maté.

Coping Patterns

“No one wakes up in the morning and decides, ‘Today, I’ll put the needs of the whole world foremost, disregarding my own,’ or ‘I can’t wait to stuff down my anger and frustration and put on a happy face instead.’” Nor are we born with these traits—instead, they are coping patterns, adaptations to preserve our connection to others, sometimes at the expense of our very lives, he warns.

We develop these traits to be accepted, in what Maté describes as the tug-of-war between our competing needs for attachment and authenticity. We need attachment to survive, as we are a tribal species, wired for connection, conforming to the needs and rules of others to secure our membership in groups.

But we also need authenticity to keep us healthy. We’re designed to feel and act on emotions, especially the “negative” ones. It’s our alarm system to survive danger. Psychiatrist Randolph Nesse, founding director of the Centre for Evolution and Medicine at Arizona State University, explains that we’ve evolved to survive, not to be happy or calm.

Low mood, anger, shame, anxiety, guilt, grief—these are all helpful responses to help us meet the challenges of our specific environments. Having loud, sensitive protective functions like emotions that sound alarms when we’re threatened isn’t a design flaw. It’s a design success.

Our emotions act as smoke alarms to match the perceived threats around us, says Nesse. This seems most obvious with emotions, like fear, that scream out warnings of danger. But even more subtle emotional experiences help us navigate threats and rewards for survival. The discomfort of a low mood is signaling that there aren’t enough rewards in our environment to outweigh the risks of being there, motivating us to seek out circumstances that are more rewarding or conserve our energy in a safe place—like in bed bingeing Netflix—until the rewards return.

Anger, too, is a necessary response to fight inequities, violations, and having our needs blocked. It’s our most effective tool to mobilize action against injustice. The biggest obstacle to social justice is not heated opposition, but apathy. And, yet, society has socialized many of us to suppress anger. Even the vilified emotion of anger’s more subtle form, resentment, is helpful. When our body and brain pick up subtle cues that our boundaries are not being respected, the resentment alarm shouts out loud and clear to assert these boundaries before we even have time to reflect on the situation.

Suppressing Vital Emotions

Yet, the need to maintain membership in our groups has led us to suppress these vital emotional signals, disarming our ability to protect ourselves, says Maté. Even more problematic, says Maté, is that conscious suppression of emotions has been shown to heighten our stress response and lead to poor health outcomes. “We know that chronic stress, whatever its source, puts the nervous system on edge, distorts the hormonal apparatus, impairs immunity, promotes inflammation, and undermines physical and mental well-being,” says Maté. And numerous studies show that a body stuck in a chronic stress response stays in an inflamed state, Maté continues, the precursor of many chronic illnesses, such as heart disease, cancer, autoimmune diseases, Alzheimer’s, depression, and many others.

Maté is careful not to use this research to blame people for their own illnesses. “No person is their disease, and no one did it to themselves—not in any conscious, deliberate or culpable sense,” he says. “Disease is an outcome of generations of suffering, of social conditions, of cultural conditioning, of childhood trauma, of physiology bearing the brunt of peoples stresses and emotional histories, all interacting with the physical and psychological environment. It is often manifestations of ingrained personality traits, yes—but that personality is not who we are any more than are the illnesses to which it may predispose us.”

Our personality and coping styles reflect the needs of the larger social group in which we develop, says Maté. “The roles we are assigned or denied, how we fit into society or are excluded from it, and what the culture induces us to believe about ourselves, determine much about the health we enjoy or the diseases that plague us.” Illness and health are manifestations of our social macrocosm, he argues.

It’s no surprise, then, that the inequities of society deeply affect our health, with those more politically disempowered or economically disenfranchised being forced to shape and suppress their emotions and needs most gravely to survive, says Maté. This means systemic change to fight inequities and focus on social justice is the foundation of improving our health, a common thread in The Myth of Normal.

At the same time, we can work to unlearn these behaviour patterns by bringing more awareness to our own emotions, signals in our bodies, and our needs, rather than automatically ignoring them in the service of others.

“The personality is an adaptation,” says Maté. “What we call the personality is often a jumble of genuine traits and conditioned coping styles, including some that do not reflect our true self at all but rather the loss of it.”

Maté describes true healing as opening ourselves to the truths of our lives, past and present. “After enough noticing, actual opportunities for choice begin to appear before we betray our true wants and needs,” he says. “We might now find ourselves able to pause in the moment and say, ‘Hmm, I can tell I’m about to stuff down this feeling or thought—is that what I want to do? Is there another option?’

“The emergence of new choices in place of old, preprogrammed dynamics is a sure sign of our authentic selves coming back online.”